Dali’s “Physiognomic Synchronism”

Salvador Dali has a mixed reputation as a master craftsman, thoughtful painter, tasteless artist and clown. His outsize ambition, common to many great masters, was unlike theirs impatient. He made use of modern media and any kind of publicity stunt to make certain that his reputation peaked in his own lifetime. He wanted to enjoy it himself, unlike Van Gogh. What has not been recognized, though, by either his critics or admirers is that Dali's deep understanding of the nature of art is not expressed in his published thoughts on art theory which, to a large extent and in common with many other artists, mislead their contemporaries.1

After developing his craft as a young student and gaining insight into art through his visual study of the masters, Dali decided to use their poetic techniques not veiled as in past art but openly and with maximum theatrical effect. Thus his many visual illusions and metamorphoses are, in fact, the same methods used by medieval and Renaissance artists including Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian. Like them, he also abided by the principle that every painter paints himself.

In the late 1950's Dali decided he could become even richer by painting the portraits of wealthy Americans. Like other artists, though, he was compelled to paint their portraits as his own alter ego without letting on. He thus publicized one of the methods of the great portraitists as though it was his own invention but did not explain its meaning. He grandly called it "physiognomic synchronism", what we on this site call "face fusion". He announced, for instance, that the face in this "portrait" of Chester Dale is fused with that of Velazquez's Pope Innocent X.

Click next thumbnail to continue

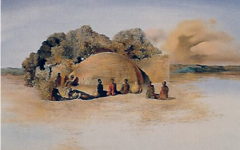

Left: Detail of Dali's Portrait of Chester Dale with His Dog Coco

Right: Detail of Velazquez's Pope Innocent X (c. 1650)

Click image to enlarge.

And so it is, most obviously in the lower half of the face. This process is exactly the same as what I have demonstrated in portraits by nearly 100 great artists, sometimes far more obviously than this. Look, for instance, at the many comparisons in the online book, Every Painter Paints Himself.

Click next thumbnail to continue

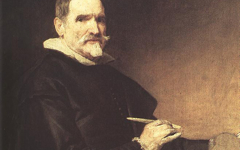

Center: Dali, From Velazquez to Hippy-Dali (photograph superimposed on Velazquez's self-portrait)

Left: Detail of Velazquez's Self-Portrait from Las Meninas

Right: Photograph of Dali

Click image to enlarge.

Dali felt such a strong sense of identification with Velazquez that he once morphed a reproduction of Velazquez's self-portrait from Las Meninas with a photograph of his own face (center image). It is even possible that Dali grew his famous mustache in emulation of the earlier Spanish master.

See conclusion below

I have little doubt that Velazquez himself used Pope Innocent X as his own alter ego though exactly how is not clear. Francis Bacon, the 20th century English artist who made many variations on the same portrait, must have thought so too.

Dali pretended that the manner in which he created Chester Dale's portrait was his own invention though he clearly knew that face fusion, or "Physiognomic Synchronism", had been used by great masters for centuries. Lucian Freud and Philip Pearlstein both continue to use it in their portraits today without mentioning it and there are probably several others too. Face fusion is just one of the many methods by which poetic artists turn a portrait of someone else into a representation of themselves. Chester Dale is therefore not just a rich American in Dali's portrait but a visual descendant of a Spanish master with whom Dali himself closely identified, one artist as representative of another.

Notes:

1. Artists have always guarded their working secrets carefully, often preventing others from watching them at work. Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists sometimes used curtains to prevent others from seeing their work. Ridofli said that Tintoretto worked in great secrecy while experimenting with his compositions. Diderot said that no-one he knew had ever seen Chardin at work. Both Matisse and Picasso are said by specialists to have given out misleading explanations of their work in order to confuse people. Picasso told Roland Renrose: "You mustn't believe what I say." See Marc Gottlieb, “The Painter’s Secret: Invention and Rivalry from Vasari to Balzac”, Art Bulletin 84, Sept. 2002, pp. 469-90; Michael Cole and Mary Pardo, "Origins of the Studio" in Cole and Pardo (eds.), Inventions of the Studio, Renaissance to Romanticism (University of North Carolina Press) 2005, p. 15; John Klein, Matisse Portraits (Yale University press) 2001, p. 19; Linda Jane Frank Ashton, Disguised Double Portraits in Picasso’s Work, 1925-1962, PhD Diss., Stanford University, 1977, pp. 19-20.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 18 Mar 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.