Dürer’s Virgin and Child (c.1491)

One of the important characteristics of sketches, at least in works by true masters, is that when more than one image is depicted on the same sheet the relationship between the motifs is rarely random; there is usually some link. On the page below, with its two seemingly unrelated drawings by Dürer, there is a subtle connection between the artist’s hand at top resting on the page and the Virgin and Child below. It may be helpful to study the drawing first before reading on.

Top: Dürer, Study Sheet for the Virgin and Child, ink on paper (c.1491) British Museum, London.

Bottom: Diagram of above with inset of Dürer's monogram enlarged.

Click image to enlarge.

Just as Dürer’s own hand spreads horizontally from the end of his unseen arm so the motif of Virgin and Child does too at the bottom of a vertical tree. And not just any tree but one signed with the artist's monogram on its trunk. The monogram, as always, is a small D nestled inside a larger A (see inset below). Now note how the form of the Virgin with her drapery resembles the A, which is wider than normal to echo her drapery; Christ nestled in her arms forms a curved D (diagram below). This echo between figures and monogram, quite common in Dürer's prints, conveys his identification with “the Virgin and Child” while also suggesting, by the use of both, that the divinity inside himself is androgynous.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Zoom in on a detail and you will see an eye-form just underneath the Virgin's hand in yet another demonstration of how eye and hand in art so often signify the unity of craft (hand) and perception (eye). This, however, is not a real eye but the inner eye of the artist's imagination positioned in front of the Virgin's womb, the locus of divine conception, a metaphor for Dürer's own conception. We are inside the artist's mind, not outside. This is confirmed by.....

Click next thumbnail to continue

Detail with diagram of Dürer's Study Sheet for the Virgin and Child with insert of detail from Dürer's Self-portrait at 26 (1497).

Click image to enlarge.

......the way in which the Virgin's drapery can also be read as a caricatural face of the artist, a mental image of himself in his imagination, fractured and partial.1 Dürer looks up from the Virgin's lap with the inner eye we just discovered positioned directly above and between his real eyes, as shown in Renaissance diagrams of the brain. The inner eye is usually behind the forehead.

Just to be clear, the Virgin and Child are a "work of art" appearing out of his mind which is why they look normal and he does not. His own face is fractured because we are inside it, not outside. This is an excellent demonstration of how normal perception is so often used in Renaissance art (and later art, too) not to depict exterior reality, as long believed, but a work of art.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Detail with diagram of Dürer's Study Sheet for the Virgin and Child with insert of detail from Dürer's Self-portrait at 26 (1497).

Click image to enlarge.

Now the various parts fall into place. Out of the artist's mental image of his own face appears:

1) his conception of the Virgin and Child as a work of art formed from his monogram

2) his inner eye (red) with which he sees them, placed over her womb and linked to her hand

3) the tree "growing" out of his far eye stamped with his monogram.

Thus, with divinity inside, the image implies that his representations of nature (tree) derive from his divine nature which is at one, as in a mystic's mind, with nature itself. His hand with its shadow touches and thus "draws" the sheet of paper itself. All is connected: conception and craft.

Click next thumbnail to continue

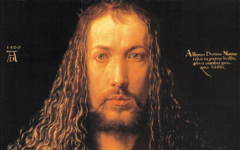

Nine years later Dürer painted his famous self-portrait as Christ. Though I find his identification with Christ here undeniable, many doubt it.2 (See the separate entry on the painting.) Yet early Christian mystics teach us, as does the Bible, that each of us has a Christ inside. Indeed our potential to become God, by uniting with the Divine, has been considered the principal goal of human life since at least the time of the Apostles.3 Some scholars see a link with the best-seller of the Middle Ages, The Imitation of Christ, but they see it as a historical development peculiar to Dürer's time when it is, instead, one of the oldest surviving ideas of Christianity.4 Annie Besant wrote in 1905: "The life-story of every Initiate into .... the heavenly Mysteries is told in its salient features in the Gospel biography. For this reason, St. Paul speaks...of the birth of the Christ in the disciple, and of His evolution and His full stature therein. Every man [& woman] is a potential Christ, and the unfolding of the Christ-life in a man [& woman] follows the outline of the Gospel story.."5

First published on 19th April 2010, this entry has been substantially revised. It is now April 11th 2013 and I have learnt a lot in the last three years.

More Works by Dürer

Notes:

1. See my explanation of Cubism, Cubism Explained, and you will see how Cubism is likely to have developed not out of nowhere, as so often suggested, but out of Picasso's insight into the meaning and hidden forms in Renaissance drapery and similar metamorphoses of forms within later styles. I intend to write more on this connection as soon as I have time.

2. Pope-Hennessey, in a now-classic book on portraiture, did not believe that Durer would paint his self-portrait as Christ. See Pope-Hennessey,The Portrait in the Renaissance (Princeton University Press) 1966, p. 129; Joseph Leo Koerner, a more recent expert, does not believe it is a portrait as Christ either but adds, rather ambiguously, that it is like paintings made of Christ. See Koerner, Dürer’s Hands (New York: The Council of the Frick Collection Lecture Series) 2006, p.43

3. See the theme Inner Tradition.

4. Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (University of Chicago Press) 1973, p. 76

5. Annie Besant, Esoteric Christianity (Quest Books) 2006, pp. 13, 17, 32-3, 98

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 11 Apr 2013. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.