Goltzius’ Mercury (1611-13)

Hendrick Goltzius' larger-than-life portrait of Mercury as a painter gives us the opportunity to interpret an image certain that it is a self-representation of the "divine" painter. Mercury, an inventor of the arts, sits with his paintbrushes and palette in one hand and a caduceus doubling as a mahlstick in the other. Such double meaning is very common, though still little-known. Mercury has vast hands, enlarged to emphasize the artist's craft, while the colors on his palette match those of the painting itself.1 He must be "Goltzius" painting the image we are looking at. Scholars still argue over Mercury's "real" identity usually suggesting that it depicts the work's patron or his son.

Click next thumbnail to continue

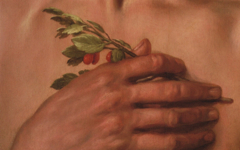

Left: Detail of Goltzius' Mercury

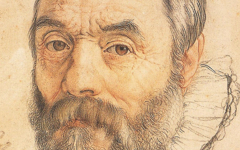

right: Detail of Goltzius' Self-portrait (c.1586-90) Metalpoint on tablet. British Museum, London

Click image to enlarge.

Nevertheless, when the face is compared to an early self-portrait of Goltzius, the similarity between the two is evident, especially the shape of the nose. This is therefore not an accurate likeness of anyone else.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Not only is Goltzius' HG monogram placed on the stone in the lower right-hand corner but its forms are repeated directly above in the composition. The arch is an 'H'; the palette below it a "G" (see diagram at left). The use of letter-forms continued in painting through the twentieth century in the work of Picasso, Matisse and others, Matisse often using H for Henri in the same way.2

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Detail of Goltzius' Mercury

Lower left and right: Detail of Goltzius' Goltzius' Right Hand, rotated and inverted. (1588) Pen and brown ink on paper. Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

Click image to enlarge.

If Mercury represents Goltzius, so must his attribute, the strutting rooster. The animal is said to signify Mercury's alert mind, an essential characteristic of a great master too. Thus the cock must be "the artist" or some aspect of him. First, see how Goltzius invested the cock's claws with the pattern of the fingers of his own right hand burnt in childhood and memorialized in a superb drawing.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Goltzius' Mercury

Center: Detail of Goltzius' Self-portrait, inverted (c.1593-5) Chalk on paper. Albertina, Vienna.

Right: Diagram of the detail at left.

Click image to enlarge.

The face of an artist is often so subtly suggested when it appears in altered form that its presence is shrouded in doubt. Here though, in addition to the claws, the rooster's wattle is shaped like Goltzius' beard while its feathers above its coxcomb copies the direction and movement of his hair, the eye in the proportionally-correct position between the two.

See conclusion below

Mercury's brushes are worth noting too. They overlap his groin, imitating the angle of an erect phallus. The metaphoric link here between sexual and mental conception is another extremely common, little-known tradition in art. Note, too, how the fabric over his groin folds into a mandorla-shaped hollow, thereby suggesting a vagina directly over his phallus, the two together conveying the androgyny of the creative mind. It is similar to how Giovanni Bellini gave the Infant Christ a vagina-like fold of skin in his leg for the same reason in The Madonna of the Pear (c.1485). None of the observations here, except the mahlstick-like caduceus, has ever been noted before. Nevertheless, I am certain that this picture is still full of veiled content, undiscovered and waiting for your perception.

More Works by Goltzius

Don't confuse illusion with likeness in portraits; they are different

Goltzius’ Portrait of Giambologna (1591) and Palma Giovane (1591)

Notes:

1. The appearance of the caduceus as a mahlstick has, of course, been noted. Lawrence W. Nichols, "The Paintings 1600-1617" in Hendrick Goltzius: Drawings, Prints and Paintings (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2003, p. 291

2. See examples under the theme Letters in Art.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 03 Mar 2013. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.