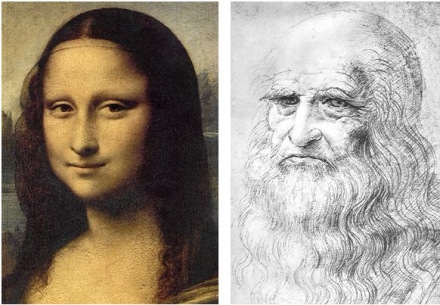

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503-7)

The most crucial piece of information about the Mona Lisa missing from standard accounts is that the proportions of her face differ from an earlier version (seen in X-rays) but are similar to Leonardo's own features as seen in a well-known self-portrait. The computer scientist who made this discovery, remarked that the position, angles and dimensions of their eyes, pupils, cheekbones, noses and mouths match precisely. The distances between the inner corners of their eyes, which she described as one of the most individual characteristics of a face, are within 2 percent of one another. Her protruding brow, moreover, is rare in women but a feature of Leonardo and most males as well.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Detail of Leonardo's Mona Lisa (c.1503-06)

R: Detail, inverted, of Leonardo's Self-Portrait (c. 1512)

Click image to enlarge.

She failed to point out, though, other similar features that support her claim. Both have significant bags under their eyes, unusual in a young woman, and long flowing hair too, possibly unique in a female portrait from the Renaissance. Women in Renaissance portraits almost always have the hair done up. Even the lighting produces similar shading in each face. Schwartz’s findings appeared in a science magazine and have been widely ignored since though one prominent curator remarked at the time: "Art history will survive this crap".2

Click next thumbnail to continue

Nor is this an ordinary portrait. Leonardo kept it with him all his life so the idea that "her father", assuming Lisa is a real person, commissioned this work is ludicrous. Just look at the setting. She sits an arm chair in front of a stone balustrade thousands of feet up into the sky above a mountain range so terrifying that it looks like no place on earth. This is also said to be the first female portrait in which the sitter is unequivocally sitting.

Kenneth Keele, a doctor and art historian, noted in 1959 that she has physical signs of pregnancy. Like women at full term everywhere, she sits well back in a comfortable chair, her back straight and well supported.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Her face and neck are also slightly puffy and her bosom full, common signs of pregnancy. The size of her abdomen is carefully concealed but her wrists and fingers are puffy too, all rings removed, something many women are forced to do late in pregnancy.

See conclusion below

Despite academic skepticism today Leonardo himself wrote that there is an automatic tendency in painters to produce figures which ‘resemble their masters’ while an acquaintance of Leonardo’s in Milan mocked him for making his figures look like himself. It therefore seems probable that the Mona Lisa is Leonardo's conception of the female muse in his own mind who gives birth to his conceptions. That's why she's pregnant and looks like him. This also explains why he never gave the portrait away. Put another way, the Mona Lisa is a personification of the creative element in his mind which, in turn, explains why the mountain range beneath her is so vast. His mind (the painting) is at one with the cosmos and is ancient too, full of wisdom. Unlike today, people in the Renaissance believed that the ancients, especially the Egyptians, were far more wise than they were, closer to the origin of man. They admired them and their understanding of humanity.

For the past three years this website has also demonstrated that major artists in almost every period since the Renaissance have fused their own features onto portraits of others bringing into doubt the long-held belief that portraits in general are the early equivalent of a photograph. See similar examples in Face Fusion and our entry on Ingres' Comtesse d'Haussonville. Keep reading the other entries too because the more you see, the more you'll see.

More Works by Leonardo

Notes:

First published online April 13th 2010; reposted Jan 7th 2013.

1. Lillian Schwartz,“The Art Historian’s Computer”, Scientific American 272, April 1995, pp. 106-11.

2. S. J. Freedberg cited in “La Chronique des Arts”, supplement to Gazette des Beaux-Arts 109, May-June 1987, p. 15

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 07 Jan 2013. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.