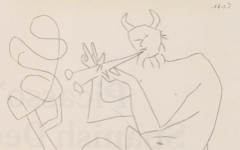

Picasso’s A Gentleman Greeting a Lady (1894-5)

This one blows my mind. I don't know if genius exists. Many think not.1 Yet Picasso, at thirteen years of age, seems to have known some secrets of true art that many so-called experts never have. At the very least the sketch below provides fascinating insight into the artistic development of a great painter.

Picasso, A Gentleman Greeting a Lady (June 1894) Watercolor on paper. Museu Picasso, Barcelona

Click image to enlarge.

There is overwhelming evidence that the adult Picasso formed many objects in his art into the shape of the letter P. Unknown to the specialists, artists like Raphael have been doing likewise for centuries. Probably only readers of EPPH know this.2 Yet in this very early drawing from 1894 the young adolescent Pablo did the same. If the dating is correct, he was not yet fourteen.

Click next thumbnail to continue

The artist's name at the time was Pablo Ruiz, as he signed himself in the lower right corner. (Ruiz was his father's family name.) Note that Pablo signed this sheet even though it was just a page in his sketchbook, one among many. Most are not signed. Yet the man forms the letter P and the woman an R. For comparisons with earlier great art, see the many examples under the theme, Letters in Art.

Click next thumbnail to continue

He was really Pablo Picasso Ruiz, his mother's name in the middle, though he was familiarly known as Pablo Ruiz. He later dropped Ruiz for reasons explained before, reasons which remain largely unknown.3 He had, though, another purpose as I have just discovered. Pica is Spanish for a long pole with a sharp end and he painted a picador, his first painting in oil, at the tender age of nine (left). The lance, notably, is missing.4 Scholars have wondered why he preferred picadors to matadors. This is possibly why.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Detail of Picasso's A Gentleman Greeting a Lady with a variety of his signatures

Click image to enlarge.

Now it seems that the P of his adult signature was even designed to resemble a pica with ball on top and sharp point at bottom like the man's cane. If so, the drawing represents Pablo (the man), Ruiz (the woman) with the cane, partly between them, as Picasso.

Click next thumbnail to continue

In a final thought, it is worth noting that he turned his initials into a man and a woman, suggesting that even then he sensed the importance of androgyny, that the true artist and human being is made of both genders regardless of sex. He clearly understood that art is self-representational which, today, only we and artists know about. It amazes me how a 13-year old could grasp all this but it seems that he did. Pablo was, of course, no ordinary child. So it may have just come naturally.

Can we call that "genius"?

Addendum: I later discovered that Picasso did something similar two years earlier. See Picasso's The Last Bull (1892).

More Works by Picasso

There is always more in Picasso than meets the eye

Picasso’s Reclining Nude with Man and Bird (1971)

Notes:

1. Today's scholars generally argue that genius was a conception of the Romantic period and should play little part in our understanding of an artist's success. Nevertheless, no-one really claims that Picasso was not a genius, nor Michelangelo, Shakespeare and many other great poets.

2. Examples by Picasso explained on EPPH include Picasso's Three Actors (1933), illustrations for books of poems by Reverdy and Gongora (1945-8), Massacre in Korea (1951), Still-life with Flowers and a Fruit Bowl (1943), Faun Flutist (1947), Woman in an Armchair (1948), Bullfight Scene (1955) and others. That is a very poor selection because there are hundreds more, almost all unseen by scholars, including the mirrors in his paintings of Marie-Thérèse Walter. For examples by Raphael, see La Gravida (1505-6), Expulsion of Heliodorus (1511-12), Sistine Madonna (1512) and La Donna Velata (c.1516).

3. The principal reason was probably that Pegasus in Spanish, pegaso, sounds like Picasso as I explained in "Picasso’s Parade (1917) and His Mysterious Name" (2011).

4. Picasso possibly felt that, with his similarly-shaped paintbrush, he was holding the lance itself. Françoise Gilot later reported: ‘All his life Pablo had identified...his role - even his fate - with that of certain other solitary performers: the anonymous acrobats and tumblers whom he etched so poignantly....the matadors whose struggles he made his own and whose drama, whose technique even, seemed to carry over into almost every phase of [his] life and work." Picasso: Graphic Magician, exh.cat. (Stanford University: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts) 1999, p. 81; Picasso's friend, Roland Penrose, reported that the artist was concerned about painting in a live performance on camera because it would kill his spontaneity. He remarked that he would feel like a matador about to enter the arena, "a sensation that he knew already in some degree every time he started a canvas." Roland Penrose, Picasso: His Life & Work (London: Victor Gollancz) 1958, p. 362

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 05 Apr 2015. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.