Picasso’s Seated Harlequin with Red Background (1905)

Left: Picasso, Seated Harlequin with a Red Background (1905) Nationalgalerie, Museum Berggruen, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

Right: Watteau, Gilles (c.1718-19) Louvre, Paris

Click image to enlarge.

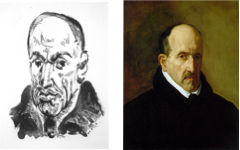

Picasso's identification with the figure of the harlequin/clown is well known (far left). Many artists have, including his great French predecessor, Antoine Watteau. Watteau's Gilles (near left) is widely recognized as a hidden self-representation of the artist.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

By the mid-nineteenth century, though, the tradition had become a vogue with even poets like Baudelaire openly acknowledging their alter ego as a clown or acrobat.2 True artists help guide the viewer towards mystic truths which many of them hint at by identifying with such marginal figures in their art: solitary, lonely virtuosos who, like the artists, deliver performances at great risk of failure. That is why the mystical poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote that "the circus is the entryway to a higher world."3

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Picasso, Seated Harlequin with Red Background (1905)

Right: Raimondi, Portrait of Raphael (c.1518)

Click image to enlarge.

Other EPPH entries show how some of Picasso's earlier paintings of women are based on a lifetime portrait of Raphael sitting on a stone ledge in a bare room (near left).4 The 1905 harlequin uses that same source, a form conveying his meaning. Picasso's alter ego, however, not only identifies with Raphael but other great masters too.

Click next thumbnail to continue

The figure lacks the accoutrements of a painter. Yet, given the source and Picasso's self-identification, none are needed. Nevertheless, his hand, flat on a blank surface, draws attention to itself. Like a pointing finger, it is a little-known gesture signifying the act of painting.5 Here it recalls Titian's hand in his self-portrait in the Uffizi which, painted with Titian's actual fingers, appear as though they are about to "paint" the blank canvas-like tablecloth, as others have noted.6

See conclusion below

The young harlequin also sits with the resigned expression of the Man of Sorrows, the dejected representation of Christ before the Crucifixion. That is not unintended because, as Jean Clair writes, Pierrot, the French clown, "can be seen to embody the myth of the crucified Christ."7 Artistic sources, the search for which has long been criticized by certain scholars as fruitless, are key to the meaning of many masterpieces, not just Picasso's. The hunt for them should be encouraged.

More Works by Picasso

Notes:

1. Dora Panofsky, “Gilles or Pierrot?: Iconographic Notes on Watteau”, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, XXXIX (1952) p.330; Theodore Reff, “Harlequins, Saltimbanques, Clowns, and Fools”, Artforum 10, Oct. 1971, pp. 30-43

2. Jean Clair, "Parade and Paligenesis: Of the Circus in the Work of Picasso and Others" in The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist as Clown (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada) 2004, p.30

3. Jean Clair, op. cit., p.25

4. Picasso's 1901 Harlequin and Blue Period

5. See entries under the theme Pointing and Touch, especially Titian's Touch which discusses the self-portrait and Picasso's Two Nudes (1905).

6. Joanna Woods-Marsden, Renaissance Self-Portraiture (Yale University Press) 1998, pp. 162-3

7. Jean Clair, op. cit., pp. 29-30

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 05 Nov 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.