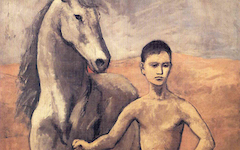

Picasso’s Two Nudes (1906)

The hand has long been recognized as an important emblem of the artist's craft. Yet when this understanding is combined with the knowledge that every great painter literally painted himself it takes on new significance. This is most evident when the hand is virtually abstracted from the subject matter, as though outside the picture ‘painting’ it.

When Picasso in 1906 drew a study for Self-portrait with a Palette, he drew his hand on the right not as in a mirror but as he himself would have seen his hand drawing his own head.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

And, in another sketch later the same year for his important painting Two Nudes, he repeated the pointing finger of one of the women above in the lower left corner as though it might again be his own finger touching (thus, drawing on) the paper.

Click next thumbnail to continue

The two women in the finished work could almost, except for their visible arms, be mirror-reflections of one another. Their legs match and their heads appear to show alternate sides of the same face. Both muscular arms, though, turn in on their bodies as though, like the hand in the first sketch shown here, they might be the artist's own outside the picture. One points, like the extracted hand in the study; the other touches its shoulder drawing attention to it. We have shown in another entry, Over-the-Shoulder Poses, that a figure looking out of the picture that way is a known form of self-representation because it is how Renaissance artists posed to paint themselves in a mirror.2

See conclusion below

These three works are just a beginning. On their own they will not convince anybody that a pointing finger is a hidden symbol for the artist's own hand painting or drawing the image. Nevertheless, keep this in mind when looking at other works because, cumulatively, the evidence becomes overwhelming. The symbol has not been recognized because so few know that every painter paints himself. Yet artists have been using this symbolism since the Renaissance. As here, in this great painting by Picasso, the pointing finger is a common symbol for a painting finger. And the whole hand, when seen from the back, touching its own body, or a flat surface, is a hidden representation of the artist's hand painting the image itself.

To expand while concluding, the heavily-built women have never been recognized for what they are precisely because conventional art historians are unaware of art's guiding principle. If they were aware of it, the resemblance of these female figures to the short, squat muscular body-type of Picasso himself would be self-evident. They are both the fertile part of "Picasso's mind", androgynous mirror-reflections of one another in the act of painting themselves. One of them, theoretically, is the artist painting; the other the painting itself. Without creative imagination, after all, that's all we ever see: the reflection of our own mind.

More Works by Picasso

Notes:

1. Picasso. The Early Years: 1892-1906 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art) 1997, p. 280

2. Michael Fried, The Moment of Caravaggio (Princeton University Press) 2010, pp. 9-37

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 17 Mar 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.