Titian’s The Tribute Money (1560-8)

Titian, The Tribute Money (1560-8), possibly begun in the 1540's. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London

Click image to enlarge.

Titian’s The Tribute Money supposedly illustrates that moment when the Pharisees asked Jesus if it was right to pay tax to the Romans and, sensing a trap, he responded that one should pay unto God those things that are God’s and unto Ceasar those that are Ceasar’s. Yet there is more to this painting than that.

First of all, Christ’s finger pointing upwards recalls Leonardo’s St John the Baptist who points upwards with one hand while gesturing to himself with the other.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Titian, The Tribute Money

Right: Detail of Leonardo, St. John the Baptist (c.1513-16)

Click image to enlarge.

As mentioned in the introduction to The Artist as Christ, this gesture seems to convey the meaning of the mystical phrase: “As above, so below”, in other words as above, so in my body, the macrocosm reflected in the microcosm. In another version of The Tribute Money (not illustrated), Titian signed his name on the collar of the Pharisee thereby clearly identifying with Christ’s questioners.

Click next thumbnail to continue

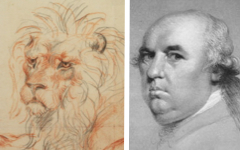

Left: Detail of Christ from Titian, The Tribute Money

Right: Detail of Engraving by Britto after Titian's lost Self-Portrait

Click image to enlarge.

In this version, though, Christ looks so like an engraving after Titian’s lost self-portrait that there can hardly be a shadow of a doubt: Titian represents himself as Christ as well. Thus, both figures become different aspects of the artist's psyche.

Look carefully and Christ’s figure seems brighter, stiffer and flatter than the Pharisees’, as if he and the background were in a different realm, a "painting". The Pharisee's body enters from the left, his torso facing the picture like the artist's once did. He is the "artist", "painting" with his gold coin the ultimate representation of himself as Christ. Titian was very concerned about payments from patrons and it has been suggested that there may be a reference to the transaction here. 1

See conclusion below

More likely, the gold symbolizes the purified soul, as it does in alchemy and other esoteric traditions. Meanwhile Zbynek Smetana has argued that circular shapes in the Renaissance may have suggested some liminal relationship about the separation of sacred and worldly realms. She was referring to circular shapes like the parapet or oculus, which was in turn transferred to coins and medals and even to decapitated heads on platters.2 She is right; the "painting" is the sacred realm of Christ; the "artist-Pharisee" is in a different reality "in the studio". The painter has painted himself, turning the subject into a mental image of its own creation.

More Works by Titian

Notes:

1. Smetana, Titian’s Mirror: Self-Portrait and Self-Image in the Late Works, PhD. Diss. (Rutgers University, NJ) 1997, pp. 58

2. ibid., p.55-6

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 22 Apr 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.