The Divine Artist

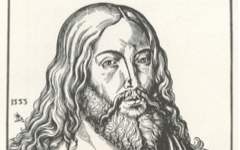

The Renaissance tendency to describe great artists as “divine” is usually considered a rhetorical device to express society’s admiration for the inexplicable talents of a great master.{ref1} Though no doubt true, many artists interpreted the term differently, not through Church doctrine as society did but through the interiorized beliefs of mystics and saints with whom they felt at one (See The Inner Tradition.) The visual evidence for this is overwhelming. Art all over Europe suggests that artists really did think of themselves as divine, not because they had vast egos (which no doubt they had) but because we are all made in the image of God, however well disguised. Just as a saint follows Christ’s path and is an image of Christ that ordinary believers can imitate, so artists undergoing the agony of creation identify with Christ’s suffering too. Their portrait of Christ is thus an image of their own self.

Most Recent Articles

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

Remember a few general principles and you will find that the art of understanding art is much easier than you might magine

Andrea Del Sarto’s Madonna in Gloria (1530)

Make sure you always know an artist's real name, the one the artist actually used. It's a very useful tool for interpretation.

Andrea Del Sarto’s St John the Baptist (c.1523)

Even anonymous art can be enjoyed through EPPH's methodology

Anonymous Antiphony from Lausanne (c.1485-90)

Why would a German pacifist like Anselm Kiefer use a Nazi salute as one of his signature gestures?

Anselm Kiefer’s Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven (1970)

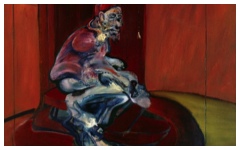

Watch the bloody and cathartic experience of painting a masterpiece

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith and Her Maidservant Slaying Holofernes

Learn how one scene can turn into another through visual metamorphosis

Bacon’s Two Men Working in a Field (1971)

An artist's identification with God was as common in the 20th century as in the Renaissance

Barlach’s The First Day (1922)

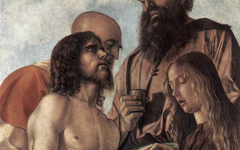

See how Giovanni Bellini used a visual pun to pass on his meaning

Bellini’s Madonna of the Pear (c.1485)

Find out how a giant Renaissance altarpiece is all about painting

Bellini’s Pesaro Altarpiece (c. 1471/4)

See how the second of a pair of paintings by Bosch is also "behind the eye."

Bosch’s St. John on Patmos (1504-5)

This masterpiece, like many before and since, must have been the source of inspiration for Picasso's Cubism. As unlikely as that may sound, it all depends on what you can see in The Birth of Venus that experts never have. You'll be one of the first...

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-6): Part Two

Learn how to note passages between one level of reality and another

Botticelli’s St. Sebastian (c.1473)

Find out how even Cézanne incorporated a mystical Christian view of life into his art

Cézanne’s Five Bathers (1885-7)

Learn how additions to a painting's narrative often provide access to the composition's underlying meaning

Caravaggio’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt (c.1597)

Cranach saw a resemblance in someone else's work and made it his own, a common practice in poetic art

Cranach’s Form of the Body of ...Jesus (1553)

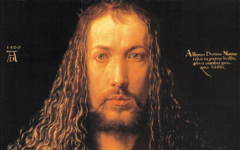

Discover how two of Dürer's images are based on his own profile

Dürer’s Death of Orpheus (1494) and Descent into Limbo (1510)

See how artists continually think on another level beyond the narrative

Dürer’s Rape of Europa and Other Studies (1494-5)

Learn how artists identified with other animals, even in the Renaissance.

Dürer’s St. Jerome in his Study (1514)

See how Durer shaped the Virgin and Child into the form of his own monogram

Dürer’s Virgin and Child (c.1491)

One of the easiest ways to find unseen features in paintings is to look for the artist's initials. Daumier included them more than most.

Daumier’s Ecce Homo (c.1849-52)

Watch El Greco's thought process over a series of paintings

El Greco’s Purification of the Temple (c.1570-1610)

For artists St Veronica is a very significant saint. She "painted" Christ.

El Greco’s Saint Veronica (c.1580)

Find out how a little knowledge of studio life goes a long way

Filippino Lippi’s Dead Christ (c.1500) and the Artist’s Turban

Self-representation was as common in the early 15th century as the 20th and today

Ghiberti’s St. John the Baptist (1412-16)

With Mercury outfitted as a painter, the viewer can interpret this image confident that the subject is art

Goltzius’ Mercury (1611-13)

Think about who you are if, for instance, you are not yourself

Goltzius’ Portrait of Jan Govertsz van der Aar as St. Luke (1614)

How tradition in art is more often based on forms than subject matter

Goltzius’ Sleeping Danae… (1603)

Think about self-referential meaning and one scene can quickly turn into another

Guercino’s St. Sebastian Succoured by Two Angels (1617)

The universal features of Frida Kahlo's art are what links her to the canon, not the details of her private life

Kahlo’s The Wounded Deer (1946)

Ordinary subjects produce extraordinary content

Lichtenstein’s Untitled or Man with Chest Expander (c.1961)

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.