Every Painter Paints Himself

Every painter paints himself, a saying first documented in the early Renaissance, has been mentioned by artists ever since. Both Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci used it, as Picasso did too; Lucian Freud and other contemporary artists still cite variations today. Yet despite its great significance to artists, art scholars rarely discuss the saying or its meaning. Those who do seem to have no choice but to deny it: painters don’t really paint themselves, they say, but their sensibility. But why would a phrase that meant so much to great masters, and still does to their followers, require re-phrasing to mean anything? The truth is, as this website demonstrates, it is the images of these visual artists that are veiled, not their words.

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

Is this merely a scene of everyday life or something more important?

Aertsen’s Cook in front of the Stove (1559)

Sometimes objects with meaning are so prominent and so large, viewers miss them

Aertsen’s Peasants by the Hearth (1556)

Altdorfer's scene of incest is an early example of a long tradition with very similar and surprising meaning

Altdorfer’s Lot and His Daughters (1537)

Remember a few general principles and you will find that the art of understanding art is much easier than you might magine

Andrea Del Sarto’s Madonna in Gloria (1530)

Make sure you always know an artist's real name, the one the artist actually used. It's a very useful tool for interpretation.

Andrea Del Sarto’s St John the Baptist (c.1523)

Even anonymous art can be enjoyed through EPPH's methodology

Anonymous Antiphony from Lausanne (c.1485-90)

Why would a German pacifist like Anselm Kiefer use a Nazi salute as one of his signature gestures?

Anselm Kiefer’s Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven (1970)

Find out, even in the work of a little-known painter, how the executioner is the artist and the victim his painting.

Antonio Campi’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian

If you keep an eye out for underlying shapes, you might even be able to guess the artist's name

Antonio da Fabriano’s St Jerome in His Study (1451)

Here is a good example of how borrowed form borrows meaning. In Artemisia's self-portrait as an Allegory of Painting, she thought of herself as a personification of Art...

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Painting (c.1630)

Learn how one scene can turn into another through visual metamorphosis

Bacon’s Two Men Working in a Field (1971)

If it looks odd, there must be a reason. See Balthus horsing around.

Balthus’ The Moroccan Rider with His Horse (1935)

In a short addendum to Part 1, see how Balthus conveyed his alter ego

Balthus’ The Mountain (1937) Part 2

Learn how to deconstruct a portrait by Balthus using a few simple principles

Balthus’ The White Skirt (1937)

Bandinelli's statue in Florence, known more for its competition with Michelangelo's David than for the statue itself, has lessons in it which help explain David

Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus (1525-34)

An artist's identification with God was as common in the 20th century as in the Renaissance

Barlach’s The First Day (1922)

See how Giovanni Bellini used a visual pun to pass on his meaning

Bellini’s Madonna of the Pear (c.1485)

Find out how a giant Renaissance altarpiece is all about painting

Bellini’s Pesaro Altarpiece (c. 1471/4)

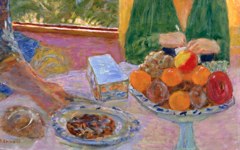

Why would a great poet just depict fruit on a platter with no other content or meaning? The answer: they wouldn't.

Bonnard’s Fruit on a Red Tablecloth (c.1943)

How Bonnard turned his creative process into a scene in modern Paris

Bonnard’s The Pushcart (c.1897)

See how the second of a pair of paintings by Bosch is also "behind the eye."

Bosch’s St. John on Patmos (1504-5)

A little knowledge of studios goes a long way to understanding art

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-6): Part One

This masterpiece, like many before and since, must have been the source of inspiration for Picasso's Cubism. As unlikely as that may sound, it all depends on what you can see in The Birth of Venus that experts never have. You'll be one of the first...

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-6): Part Two

Pastoral genre scenes, although invented by Boucher, abide by art's traditions

Boucher’s Pastoral landscape with a shepherd and shepherdess (c.1730)

Unless you knew that there might be a self-portrait in this Reclining Nude, you'd probably never see it.

Boucher’s Reclining Nude (1730’s)

This a reminder of how close the association was between writing and painting in the Middle Ages

Brother Rufillus’ Self-Portrait (c. 1170-1200)

How a seemingly extraneous figure can be the crux of the whole artwork

Burgkmair’s Archer in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (1504)

Find out how even Cézanne incorporated a mystical Christian view of life into his art

Cézanne’s Five Bathers (1885-7)

Page 1 of 11 pages 1 2 3 > Last ›

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.