Letters in Art

One little-known artistic method is letter-based, an artist’s use of their own name or initials to indicate subjectivity. A signature is conventionally considered a sign of authorship and nothing more but, as a number of scholars have pointed out within their own specialty, the careful placement of a signature adds meaning too.{ref1} This ought to be better known and considered in the interpretation of any work of art. What you need to know, though, is something even more fascinating and rarely seen by those who are not artists themselves: the hidden presence of an artist’s initials or the letters of their name. By disguising the letters as objects in nature, the viewer “reads” them as images of something else and thus misses the artists’ meaning. Study the examples here and you will see the same method in other art because, as we always emphasize, if you do not know that artists do such things, you cannot see them.

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

If an artist's first and last initials are the same, or his initial matches that of his hometown, like Lucas van Leyden's, it is more than likely to appear in his work as well.

Lucas van Leyden’s Standard-Bearer (c.1510)

This early painting by Manet has always troubled interpreters because it seems to make no apparent sense. Its explanation here, though, will help you understand paintings by Manet, Velazquez and other artists too.

Manet’s Mlle. V in the Costume of an Espada (1862)

One of the many ways artists "paint themselves" is by painting others as earlier great masters.

Manet’s Angelina (1865)

Find out how Manet's observations of scenes in Parisian cafés are really something else entirely

Manet’s Café-Concert (1878)

Familiarize yourself with an artist's early copies after other masters. They will be a key to later work.

Manet’s Croquet at Boulogne (1871)

Art scholars have sometimes wondered why the execution squad in Manet's Execution of Emperor Maximillian are so unrealistically close to their target. Indeed, on close inspection, their rifles are aimed as though they would miss.

Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximillian (1867-8)

Leran how the initials of an artist's name can appear anywhere. Not all is what it seems.

Manet’s Monet Painting on His Studio Boat (1874)

Don't forget to imagine what can't be seen: the artist's viewpoint

Manet’s Music in the Tuileries (1862)

See how Manet's identification with Courbet is recognized by a later artist who then used it in his portrait of yet another artist.

Manet’s Portrait of Courbet

Skating on ice is like drawing lines on the mirrored surface of the artist's mind

Manet’s Skating (1877)

This magical composition hides a complex thought of seeming effortless construction: a masterpiece of the first order

Manet’s Tragic Actor (1865-6) Part 1

An early example of how Manet turns a modern woman, and his future wife, into an artist

Manet’s Woman with a Jug (1858-60)

Unless there are dogs or cats in the picture, we tend to look at the humans more than the animals. Don't. Artists are often animals.

Marino Marini’s Poster for an Exhibition (1959)

Why did Picasso choose this painting for himself? What did he see in it?

Matisse’s Marguerite (1906-7)

See how Matisse himself appears in even a simple drawing of an unidentified model

Matisse’s Seated Young Woman in a Patterned Dress (1939)

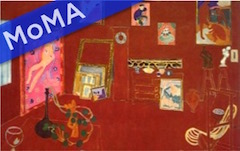

Look for the eyes. Then the face. Never forget to look for them because you can find them anywhere in art.

Matisse’s The Window (1916)

See how Notre-Dame, France's cathedral and symbol of the nation, becomes Matisse's

Matisse’s View of Notre-Dame (1914)

Miró's variations on his name inspired one image after another, all unseen until now. Take a look.

Miró‘s Name in Miró‘s Art (1937-69)

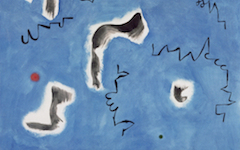

See how Miró wrote his name in large letters across his canvas yet left his viewers blind

Miró‘s Painting (1933)

Miró's inventive and individualistic style, however modern, is merely a complement to his deep traditionalism. And that's as it should be.

Miró‘s Painting / The Circus Horse (1927)

Discover yet another example of how Miró's composition is based on his own name

Miró‘s Potato (1928)

Consistency is often the hallmark of a great artist. This drawing by the 17-year old Miró is a remarkable demonstration of it.

Miró‘s The Podiatrist (1901)

Did you know that....? There's so much to see for the first time, even in the most familiar images

Munch’s The Scream (1895)

Many were scandalized by this painting in the 1990's yet still missed the "real" scandal!

Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1996)

Peale's American portraits have more in common with great European art than is generally accepted.

Peale’s Portrait of George Washington (c.1780)

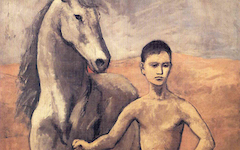

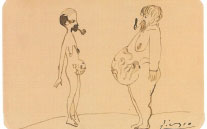

"Genius" is derided nowadays in academia but, if there is no such thing, how did a 13-year old Picasso know what art historians never have?

Picasso’s A Gentleman Greeting a Lady (1894-5)

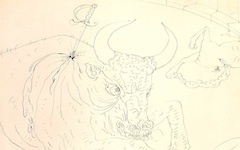

Picasso kills a bull with his own paintbrush while indicating his divinity.

Picasso’s Bullfight Scene (1955)

Two protagonists in one painting must both represent the artist. It's a given in art so it's your job to find out how.

Picasso’s Cat Catching a Bird (1939)

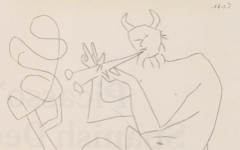

Learn to recognize the letters of Picasso's signature, a key to many of his works

Picasso’s Faun Flutist (1947)

Learn how Picasso bases an image on the letters of his signature

Picasso’s Musician, Dancer, Goat and Bird (1959)

See how Picasso uses YO to symbolize a girl and a bull as apsects of himself

Picasso’s Portrait of a Girl and a Bull

Not a particularly successful picture but an excellent learning tool

Picasso’s Portrait of Jacqueline (1965)

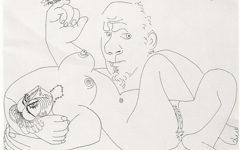

What looks like nonsense from Picasso - pregnant men with breasts - make sense if you see it the way Picasso did.

Picasso’s Pregnant Smokers (1903)

There is always more in Picasso than meets the eye

Picasso’s Reclining Nude with Man and Bird (1971)

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.