Swords and Weapons as Brushes

Weapons as symbols for an artist’s brush are the single most overlooked characteristic of Western art. The world’s museums are full of masterpieces in which ‘artists’ are secretly at work ‘killing’ their subjects, often themselves. In fact, so successfully have great masters hidden their underlying theme that scarcely any of them have ever been recognized. There are, however, hints in the literature and in prints about painting. In the 15th century L. B. Alberti had suggested a connection between archery and painting.{ref1} In other treatises and allegories on the subject it has been noted that ‘armor and battle are frequently associated with the artist and the Art of Painting’.{ref2} A 16th century critic described Michelangelo’s brush as a ‘lance’ while Rembrandt and others donned military armor in their self-portraits. Vasari likewise used terms with military connotations to illustrate Michelangelo’s approach to painting the Sistine chapel and eventually announced that the sculptor had ‘vanquished’ the medium.

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

More evidence that even at a very early date Lichtenstein was on the path of the Old Masters

Lichtenstein’s Mail-Order Foot (1961)

Once again, see how the hilt of a sword signs the artist's name

Lotto’s Judith with the Head of Holfernes (1512)

Learn how "every painter paints" himself makes logical sense of even the most confused compositions

Lotto’s Virgin and Child with Saints Roch and Sebastian (c.1522)

If an artist's first and last initials are the same, or his initial matches that of his hometown, like Lucas van Leyden's, it is more than likely to appear in his work as well.

Lucas van Leyden’s Standard-Bearer (c.1510)

This early painting by Manet has always troubled interpreters because it seems to make no apparent sense. Its explanation here, though, will help you understand paintings by Manet, Velazquez and other artists too.

Manet’s Mlle. V in the Costume of an Espada (1862)

This curious painting by Manet makes little sense until the viewer uses the idea that every painter paints himself

Manet’s Boy with a Sword (1861)

Art scholars have sometimes wondered why the execution squad in Manet's Execution of Emperor Maximillian are so unrealistically close to their target. Indeed, on close inspection, their rifles are aimed as though they would miss.

Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximillian (1867-8)

There is more to the Tragic Actor than meets the eye. Find out what's there that others cannot see.

Manet’s Tragic Actor (1865-6) Part 2

See how Mantegna like many other masters uses the Execution of St Sebastian to convey the idea that 'every painter paints himself.'

Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian (1480)

In this 1490 version of Saint Sebastian in the Ca' d'Oro, Venice, Saint Sebastian has one leg in the "picture", so to speak, framed by the marble, with the other stepping forward out of it into our space.

Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian (1490)

Arrows in art are often "brushes", especially with inconsistencies on the literal level

Memling’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (c.1475)

A mysterious drawing that has never made sense is now explained simply

Michelangelo’s Archers Shooting at a Herm (c.1530) Part 1

There is yet more meaning in the drawing as we see in Part 2 of this analysis

Michelangelo’s Archers Shooting at a Herm (c.1530) Part 2

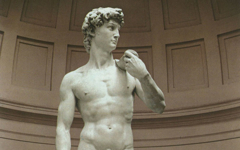

David is not difficult to understand as long as you use the correct perspective

Michelangelo’s David (1501-04)

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment is a composition so full of incidents inconsistent with an orthdox reading of the Last Judgment and theology that experts often have trouble explaining them.

Michelangelo’s St. Sebastian in The Last Judgment

The theme of an executioner with a decapitated head as a visual metaphor for a painter continues to this day.

Norbert Bisky’s Youths with Decapitated Heads (2006-08)

Indian art though always separated from Western art, in both museums and scholarship, may have more in common with it than ever thought before.

Payag’s Shah Jahan Riding a Stallion (c.1628)

Peale's American portraits have more in common with great European art than is generally accepted.

Peale’s Portrait of George Washington (c.1780)

In this early painting of St. Sebastian by Perugino the artist signed his name as though it was the arrow: "Opus Peruginus Pinxit."

Perugino’s Bust of St. Sebastian (1493)

Picasso kills a bull with his own paintbrush while indicating his divinity.

Picasso’s Bullfight Scene (1955)

Learn how Picasso used swords as "paintbrushes", "etching needles" and other tools of the trade

Picasso’s Swords and Knives

Yet more evidence that the adolescent Picasso understood the self-referential paradigm of art

Picasso’s The Last Bull (1892)

Learn how Picasso used another artist's name to represent his own identification with the great masters of the past

Picasso’s Three Actors (1933)

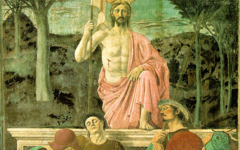

A resurrection by its very name suggests two realities: the old and the new, the illusory and the real.

Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection (c.1458)

We have seen elsewhere how artists use the arrows of St. Sebastian, the saint's identifying attribute, as symbols for their own paintbrushes.

Raphael’s Galatea (1512)

See how Rembrandt turned an anatomy lesson into a scene in his studio (in his mind).

Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp (1632)

How the setting is so rarely what you think....you must think differently

Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath (1643)

See how Rembrandt concisely expresses the underlying idea of art in a Roman myth

Rembrandt’s Lucretia (1666)

Several clues, easy to spot, reveal the true underlying meaning of two similar masterpieces

Rembrandt’s Man in Armour (1655) and Minerva (c.1655)

How Rembrandt's method, and that of great artists in general, is present in his earliest extant painting

Rembrandt’s The Stoning of St. Stephen (1625)

The presence of a mystery in an artwork, intentionally made mysterious by the artist, does not mean that the mystery cannot be solved. Mysteries are made to be resolved.

Rembrandt’s Woman with the Arrow (1661)

Discover a common way how artists demonstrate their identity with their protagonist. You can use the method to interpret other paintings by other artists.

Reni’s David with the Head of Goliath (1605)

The Inner Tradition as practised by a Catholic artist....

Rouault’s Miserere: Eternally Scourged (1922)

See how Rubens turned a variation on a Leonardo composition into a scene of creative struggle in his own mind

Rubens’ Battle of the Standard (c.1600) after Leonardo

Learn how one artist copies another and makes it his own

Rubens’ Copy of Titian’s Charles V in Armor with a Drawn Sword (c.1603)

How even in the 15th century an artist thought of himself as Christ...and said so.

Schongauer’s Christ Carrying the Cross (c.1475)

One of Titian's masterpieces, it was destroyed by fire in 1577 but recorded in this engraving. Its secret, though, lives on.

Titian’s Battle of Cadore (1538-9)

Even in the remaining fragment of a much larger canvas there is still much to see

Titian’s Noli Me Tangere fragment (1553-4)

Look for the artist's initials where you might expect them

Titian’s Portrait of Ippolito de’ Medici (1533)

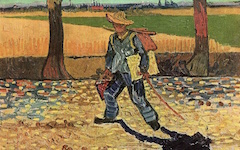

A spiritual journey is one of the basic plots of literature and a common metaphor in both philosophy and religion. Why not art?

Van Gogh’s On the Road to Tarascon (1888)

See how Velazquez portrays the artist and his art and then apply the lesson learned elsewhere

Velazquez’s Prince Baltasar Carlos with a Dwarf (1632)

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.