Lichtenstein’s Alka-Seltzer (1966)

Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) is often dismissed as a minor American painter lacking in craft and imagination. Imitating mechanical draughtsmanship, his style hides evidence of his hand and brushstroke, a process previously prized by the Abstract Expressionists. Interiority often seems absent from Lichtenstein's works while his drawing style is seen by some as "crude, amateurish and unsophisticated."2 His supporters, too, often rely on meaningless formal analysis, noting the mastery of his compositional technique.3 Graham Bader, more acute than most, identified within some early drawings "an orchestrated reflection on the nature of the artistic activity itself."4 Unaware of that analysis and puzzled by Lichtenstein's continuing significance, I recently began to study his works, quickly realizing that, contrary to my expectations, Lichtenstein's art is embedded with philosophical meaning and in tune with the Western canon. His works are self-reflexive because, as both philosophy and art teach, the only valid path to wisdom is inside you.

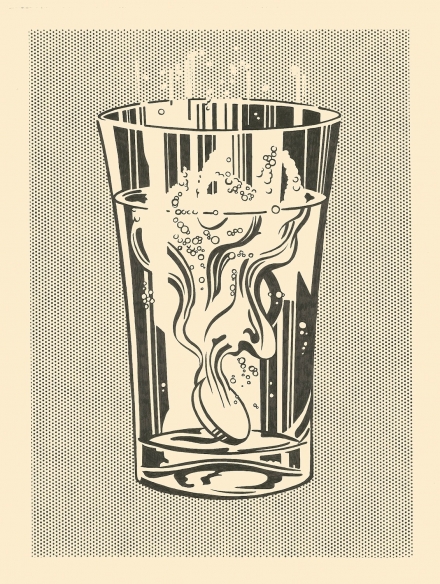

Lichtenstein, Alka-Seltzer (1966) Graphite pencil, pochoir, and lithographic rubbing crayon on paper. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Click image to enlarge.

Here, for instance, is an early drawing, Alka-Seltzer, seemingly copied from an advertisement for the well-known medicine. The image is, of course, cleaned up and beautifully positioned on an even ground of his signature Ben-Day dots. Isabelle Dervaux writes that it relates to the artist's "mid-1960s preoccupation with the representation of light reflection and moving water" while Mark Pascale significantly noted a link between the trail of the descending tablet and Lichtenstein's paintings of brushstrokes. At least the latter, like Bader, found a link to art.5

Click next thumbnail to continue

Detail of Lichtenstein's Alka-Seltzer between photographic details of Lichtenstein's face late in life and in the 1960's.

Click image to enlarge.

The falling tablet, it turns out, is the artist's broad "chin" with the trails of water above suggesting his prominent nose (see diagram and photos for comparison.) A thick, dark curve to the right resembles no facial feature at all but does, perhaps, hint at the circle of an eyeball beyond his nose.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Out of the artist's caricature-like head come bubbles of inspiration and the trails of water intentionally similar to his images of brushstrokes. The artist, as shown on this site for so many different artists, is mentally conceiving the very image we are looking at. The white bubbles in his head (or glass) do not simply "provide a humorous echo of the black Benday dots", as Dervaux proposed, but are their negative representation during the creative process.6 Above the glass they morph into the black dots.

Click next thumbnail to continue

To ensure that the perceptive viewer recognizes that the metamorphic caricature is intentional, Lichtenstein structured the forms within the glass into the letters of his first name: ROY. The O is that mostly hidden non-descriptive form hinting at an eye while the Y is fractured as though the effervescence and light striking the glass are in the process of forming his name.

Click next thumbnail to continue

That is not all. Roy is a variant of the French word for king. Its modern spelling is roi and it is an alchemical symbol for the mind at its most pure, the goal towards which artists and other spiritual seekers strive. This type of content is so at odds with the general view of Lichtenstein's art that his comment about the changes he used to make to his meaningless sources in commercial illustration takes on significance. "The difference is often not great", he said, "but it is crucial."7 And so it is.

See conclusion below

Lichtenstein was also asked if his art meant anything. He avoided a direct answer but replied that he did indeed care about what other artists thought. He added that the audience for art beyond artists (poetic artists, I presume) was so small that most people just looked at the surface. "I think the people who read art", he said, "are still a very small group.” He was, of course, right again but, here, we're trying to change that!

It is important to read analyses of other works here by Litchenstein to gain a fuller understanding of his achievement.

More Works by Lichtenstein

Notes:

1. Isabelle Dervaux commented that "Lichtenstein's stock figures and apparent impersonality of style manifest a refusal of interiority for the sake of drawing per se." Dervaux, "Baked Potatoes, Hot Dogs, and Girls' Romances: Roy Lichtenstein's Master Drawings" in Roy Lichtenstein: The Black-and-White Drawings, 1961-1968 (New York: Morgan Library and Museum) 2011, p. 26

2. April Kingsley, “Roy Litchenstein’s Drawings. New York, Museum of Modern Art”, Burlington 129, Jun. 1987, pp. 419-20

3. Mark Pascale, “Alka Seltzer”, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 30, No. 1, Notable Acquisitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, 2004, p. 90

4. Graham Bader, "Drawing Touch" in Roy Lichtenstein: The Black-and-White Drawings, 1961-1968 (New York: Morgan Library and Museum) 2011, pp. 43-50, esp. 50.

5. Pascale, p. 90

6. Roy Lichtenstein: The Black-and-White Drawings, 1961-1968 (New York: Morgan Library and Museum) 2011, p. 184

7. Cited in Dervaux, p. 19

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 20 Jan 2013. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.