The Inner Tradition

This is perhaps the most difficult part of your journey towards looking at art through the artist’s own eyes, especially if you believe in Christ and belong to an established Church. It is important because so much of Western art, especially in the Renaissance, depicts religious themes. Few people know that there are at least two ways of reading the Bible: the conventional exoteric tradition favored by the various Churches and the esoteric tradition practised, often in secrecy, by individual mystics, saints, prophets, poets and visual artists too. It is little known because over the centuries many of its practitioners have been denounced as heretics by the Church and their writings destroyed. Nevertheless their approach was practised by many of the early Church Fathers, including Origen in the second century AD. In the exoteric tradition the Bible is read at face value as though it is an historical account of divine events. This makes many who follow Church doctrine into believers who must suspend their critical faculties to accept, paradoxically, the unbelievable.

Most Recent Articles

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

Altdorfer's scene of incest is an early example of a long tradition with very similar and surprising meaning

Altdorfer’s Lot and His Daughters (1537)

Remember a few general principles and you will find that the art of understanding art is much easier than you might magine

Andrea Del Sarto’s Madonna in Gloria (1530)

Make sure you always know an artist's real name, the one the artist actually used. It's a very useful tool for interpretation.

Andrea Del Sarto’s St John the Baptist (c.1523)

Even anonymous art can be enjoyed through EPPH's methodology

Anonymous Antiphony from Lausanne (c.1485-90)

Why would a German pacifist like Anselm Kiefer use a Nazi salute as one of his signature gestures?

Anselm Kiefer’s Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven (1970)

An artist's identification with God was as common in the 20th century as in the Renaissance

Barlach’s The First Day (1922)

See how Giovanni Bellini used a visual pun to pass on his meaning

Bellini’s Madonna of the Pear (c.1485)

See how the second of a pair of paintings by Bosch is also "behind the eye."

Bosch’s St. John on Patmos (1504-5)

A little knowledge of studios goes a long way to understanding art

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-6): Part One

Find out how even Cézanne incorporated a mystical Christian view of life into his art

Cézanne’s Five Bathers (1885-7)

"Mistakes" in representing reality are cues to the scene's underlying meaning

Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of St. Ursula (1609-10)

See how Caravaggio conveyed ideas about art in a simple image which Artemisia Gentilleschi then transformed into her own self-portrait

Caravaggio’s Narcissus (c.1597-9)

An excellent example of the invisible mirror in art

Carracci’s Christ appearing to St Peter on the Appian Way (1601-02)

An easy-to-recognize demonstration of how artists fuse the studio and their subject into one image

Coello’s St. Louis Worshipping the Holy Family (c.1665-8)

See how Cranach represents himself as an evil man executing "his painting" of spiritual perfection.

Cranach’s Martryrdom of St. Barbara

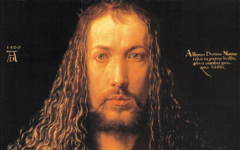

Discover how two of Dürer's images are based on his own profile

Dürer’s Death of Orpheus (1494) and Descent into Limbo (1510)

Learn how artists identified with other animals, even in the Renaissance.

Dürer’s St. Jerome in his Study (1514)

See how Durer shaped the Virgin and Child into the form of his own monogram

Dürer’s Virgin and Child (c.1491)

One of the easiest ways to find unseen features in paintings is to look for the artist's initials. Daumier included them more than most.

Daumier’s Ecce Homo (c.1849-52)

For artists St Veronica is a very significant saint. She "painted" Christ.

El Greco’s Saint Veronica (c.1580)

What you can see in a self-portrait when you think creatively. Indeed it's your job to become the painter...

Gauguin’s Self-portrait with a Palette (c.1893-4)

Self-representation was as common in the early 15th century as the 20th and today

Ghiberti’s St. John the Baptist (1412-16)

True artists make their art contemporary while remaining solidly traditional

John Sloan’s Hanging Clothes (c.1920)

Even as a 19-year old Frida Kahlo was in tune with the Inner Tradition

Kahlo’s Self-portrait in a Velvet Dress (1926)

Everyone agrees that Frida Kahlo painted herself.....but within which tradition? Psychological and surrealist or esoteric?

Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Portrait of Dr. Farill (1951)

The universal features of Frida Kahlo's art are what links her to the canon, not the details of her private life

Kahlo’s The Wounded Deer (1946)

This angel is not just a charming detail but central to the whole conception of the altarpiece

Lotto’s San Bernardino Altarpiece (1521)

Joseph, worth only a cameo appearance in the Bible, is a major star in visual art. Cast as a narcoleptic, he falls asleep in one image after another without any art historian, to my knowledge, pausing to ask: Why does he sleep so much?

Mantegna’s Adoration of the Shepherds (c.1450-51)

Durer's 1500 self-portrait as Christ is considered most unusual. He was not alone.

Mantegna’s Ecce Homo (c.1500)

Look for the eyes. Then the face. Never forget to look for them because you can find them anywhere in art.

Matisse’s The Window (1916)

An early example of how art is a guide to what we now call "self-knowledge".

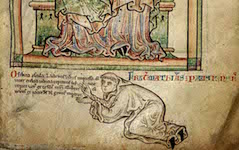

Matthew Paris’ Virgin and Child with Artist Kneeling (c.1250)

Find out what the studio and Golgotha have in common

Mengs’ Christ on the Cross (1761-9), Goya’s and Francis Bacon’s too

Michelangelo's strange scene of a battle is not what it seems

Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina (1504)

Always look for what is odd. It's often there where you'll find a breakthrough in meaning

Michelangelo’s Christ in the Last Judgment (1534-41)

Learn how Michelangelo's The Dream of Human Life, traditionally interpreted as an allegory of virtue and vice, is instead a visual metamorphosis of the artist's head.

Michelangelo’s The Dream of Human Life (c.1533)

Michelangelo's first great masterpiece is widely misunderstood. Like art in general, it is an expression of the creative moment.

Michelangelo’s Vatican Pieta (1498-99)

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.