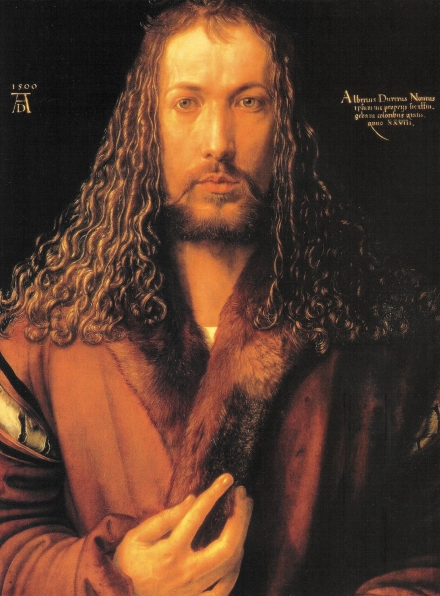

Dürer’s Self-portrait as Christ (1500)

In the year 1500 Albrecht Dürer painted his self-portrait as Christ. It is one of the few portraits of Christ up to that time so readily identifiable as a self-portrait. Yet he was not alone. As I have shown elsewhere, in the same year or close to it, both Mantegna and Perugino portrayed Christ with their own features and many artists did so subsequently including Titian, Rembrandt and Van Dyck. Art historians, unaware of the Inner Tradition, have tried to defend Dürer against charges of blasphemy. Erwin Panofsky asked in the 1940's: “How could so pious and humble an artist as Dürer resort to a procedure which less religious men would have considered blasphemous?”1 Yet Moriz Thausing, a German scholar, already had it right in 1876 when he described the painting as “Albrecht Dürer, by himself, seen frontally, the young Christ of art...”2 Recent scholars have linked Dürer's portrait to the Imitatio Christi, the idea promoted by St. Francis among others that the good Christian should imitate Christ’s life.3 They see it, though, as a historical moment, a change in understanding, a concept peculiar to the time.

I have already shown how great artists often change the features of their sitters to more closely match their own.4 Joseph Leo Koerner, a noted authority on Dürer, has similarly shown that Dürer changed his hair color in this self-portrait to more closely resemble what the Son of God was then meant to look like. He has made some other interesting observations too.

Click next thumbnail to continue

He has noted that Dürer’s hand and finger contribute much to the painting’s feeling of space because without the hand the portrait would appear flat. He then describes the hand as “the active hand” celebrating “the creative tool of his [Dürer's] trade”.5 I would say that the extended finger symbolizes his unseen paintbrush creating the portrait which is why the finger appears to rest on a flat surface. Paintings are flat.

Click next thumbnail to continue

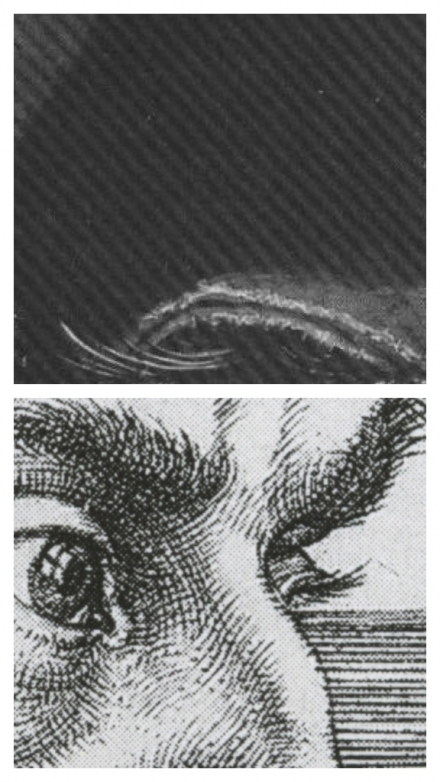

Detail of the artist's right-hand sleeve from Dürer's Self-portrait as Christ

Click image to enlarge.

Koerner also noted that Dürer’s right hand (assuming the image is a mirrored reflection) disappears below the frame and pointed out a detail so close to the lower edge it is often missing in reproduction: the edge of Dürer’s sleeve with individual hairs protruding from it. (The only available image, at left, is in black-and-white.) Koerner argues that it draws attention to the action of Dürer's painting hand, which it does, but there is more. The hairs and fabric on the hem of his sleeve resemble on another level an "eye with its eyelashes."

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Detail of sleeve at lower edge from Dürer's Self-portrait as Christ (1500)

Bottom: Detail of Dürer's Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon (1526) Engraving on paper

Click image to enlarge.

The care with which Dürer managed details like the fur emerging from the sleeve (top) is evident from his much later Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon in which the far eyelash (bottom) is ever so carefully positioned above the line of shading in the background. The visual comparison at left strongly supports the idea that the hairs of fur near where Dürer's/Christ's hand would be are, on a deeper level, the hairs of an eyelash. His own hand and eye, Durer suggests, are emanations of the divine and work like one, eye and hand united. Thus, the portrait of Christ situated above that “eye” is a depiction from inside his own mind.

More Works by Dürer

Notes:

1. Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton University Press) 1971, p. 43

2. Few art historians I know of come as close to my approach as Moriz Thausing's. He believed that artists depict all subjects in their own image, as great writers and poets do too. He wrote: “[Art] is the total subjectification of the object, the consumption of the master in the material of his images.” Thausig, Dürer. Geschichte seines Lebens und seiner Kunst (Leipzig) 1876, p.364 cited in Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (University of Chicago Press) 1973, p. 74

3. Koerner, ibid., p.76

4. See emtries under the theme "Portraiture".

5. Koerner, ibid., pp. 141-2

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 15 Jul 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.