Insight-Outsight

In art, as in language, there have always been two forms of vision, sight and insight. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance "reality" was not considered to be in this world which is ever-changing and poorly perceived by our senses. Almost everyone in the Renaissance, regardless of their sect, thought that true reality was elsewhere where forms remained pure and constant. A popular tract, published by Martin Luther in 1516, argued that the right eye had the power to see into the eternal while the left eye saw the material world we know. The two together, though, cannot function as they ought to simultaneously. The left eye must shut off this world for the right eye to see eternity. This tradition has been widely used ever since and is still practiced today. It has, however, hardly ever been recognized, with James Hall a rare and notable exception.{ref1} Among secular artists in tune with the Western tradition, an open eye signifies perception of this world, a closed one insight into the imagination.

Most Recent Articles

Many were scandalized by this painting in the 1990's yet still missed the "real" scandal!

Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1996)

All Articles (Alphabetical by Artist, then Title)

Even anonymous art can be enjoyed through EPPH's methodology

Anonymous Antiphony from Lausanne (c.1485-90)

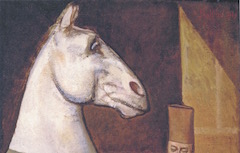

If it looks odd, there must be a reason. See Balthus horsing around.

Balthus’ The Moroccan Rider with His Horse (1935)

An artist's identification with God was as common in the 20th century as in the Renaissance

Barlach’s The First Day (1922)

See how Basquiat's Boone turns facial resemblance on its head and becomes Basquiat.

Basquiat’s Boone (1983)

Why would a great poet just depict fruit on a platter with no other content or meaning? The answer: they wouldn't.

Bonnard’s Fruit on a Red Tablecloth (c.1943)

This masterpiece, like many before and since, must have been the source of inspiration for Picasso's Cubism. As unlikely as that may sound, it all depends on what you can see in The Birth of Venus that experts never have. You'll be one of the first...

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-6): Part Two

How a seemingly extraneous figure can be the crux of the whole artwork

Burgkmair’s Archer in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (1504)

How others have already recognized Cézanne's late portraits as "portraits" of himself.

Cézanne’s Portrait of Geffroy (1895) and later portraits

See how a simple drawing is not just a photographic record of the Cézanne's face

Cézanne’s Self-Portrait Drawing (c.1878-80)

One of my first discoveries remains, for me, an object lesson in art. Perhaps for you too.

Carpaccio’s St. George and the Dragon (1502)

A long-mysterious image succumbs to interpretation if seen through a different paradigm

Carrington’s Self-portrait (c.1937-8)

How Daumier turned a kettle-drum into symbols...

Daumier’s The Orchestra.. ..During A Tragedy (1852)

See how the meaning behind this image changes our entire understanding of Degas' oeuvre

Degas’ Woman Drying Her Foot (1885-6)

Discover the secret under Goliath's helmet then know what to look for

Donatello’s Davids and Goliaths (1410-1440’s)

See how a contemporary artist still uses the language of the great masters

Elizabeth Peyton’s Portraits (1991-)

See how Hals used his monogram to signal an alter ego

Frans Hals’ Portrait of a Gentleman, half-length, in a black coat (early 1630’s)

What you can see in a self-portrait when you think creatively. Indeed it's your job to become the painter...

Gauguin’s Self-portrait with a Palette (c.1893-4)

True artists make their art contemporary while remaining solidly traditional

John Sloan’s Hanging Clothes (c.1920)

If a hand is missing, can it still represent the artist's craft?

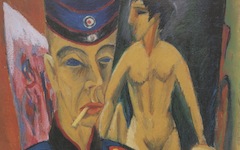

Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as Soldier (1915)

History and the politics of the moment never trumps self-knowledge and self-reference as the 'sine qua non' of art

Kollwitz’s “Down with Abortion Clause” Poster (1924)

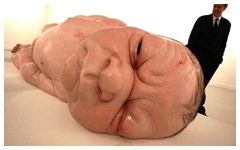

Unless there are dogs or cats in the picture, we tend to look at the humans more than the animals. Don't. Artists are often animals.

Marino Marini’s Poster for an Exhibition (1959)

Discover yet another way that artists convey their dual perception

Matisse’s Self-Portrait Sketching (1900)

There is yet more meaning in the drawing as we see in Part 2 of this analysis

Michelangelo’s Archers Shooting at a Herm (c.1530) Part 2

See how Michelangelo continued tradition while he changed it

Michelangelo’s Study for a Bronze David (c.1502-03)

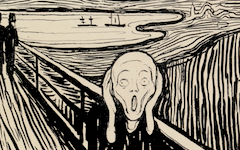

Did you know that....? There's so much to see for the first time, even in the most familiar images

Munch’s The Scream (1895)

Many were scandalized by this painting in the 1990's yet still missed the "real" scandal!

Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1996)

More evidence that an illusionistic portrait is not necessarily a depiction of what we normally see

Parmigianino’s Man with a Book (1523-4) with works by Titian and Michelangelo too

Two protagonists in one painting must both represent the artist. It's a given in art so it's your job to find out how.

Picasso’s Cat Catching a Bird (1939)

See how Picasso turns one scene into another in ways that have never been seen

Picasso’s Five Figures in a Boat (1909)

Picasso turned the face of a Spanish queen into a townscape by fusing the two

Picasso’s Le Vert-Galant (1943)

Not a particularly successful picture but an excellent learning tool

Picasso’s Portrait of Jacqueline (1965)

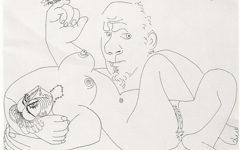

There is always more in Picasso than meets the eye

Picasso’s Reclining Nude with Man and Bird (1971)

Genres are an artificial classification of little meaning. For instance, as here, still-life without life would be still-born.

Picasso’s Still-Life with Door, Guitar and Bottles (1916)

Ignore the title of a painting; they can lead you far astray

Picasso’s Woman with Clasped Hands (1907)

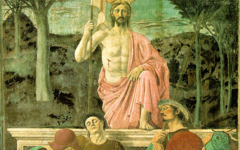

A resurrection by its very name suggests two realities: the old and the new, the illusory and the real.

Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection (c.1458)

See how an Impressionist painting is really constructed

Pissarro’s View of the Tuileries. Morning (1900)

© Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.