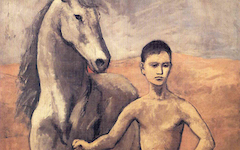

Picasso’s Cat Catching a Bird (1939)

Picasso, Cat Catching a Bird (1939) Oil on canvas. 81 x 100 cm. Musée Picasso, Paris.

Click image to enlarge.

Picasso’s Cat Catching a Bird is an unusual subject for art. Superficially it doesn’t seem to mean much but underneath, within art’s tradition, there is a lot. The cat represents Picasso.1 Her mismatched eyes - white contoured in black and vice versa - are a poet’s: one is open to the exterior world, the other closed for insight.2 She is pregnant and pregnancy, as readers know, is commonly used in poetry and art for a mind conceiving ideas.3

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Detail and diagrammatic detail of Picasso's Cat Catching a Bird

Center: Two examples of Picasso's signature

Bottom: Deatil of Picasso's Cat Catching a Bird

Click image to enlarge.

Within the cat’s left eye is an odd sight: a lowercase A in perfect typeface, a letter in Picasso’s name (top). It’s an intentional hint that other letters may be found elsewhere such as the P in his wandering nostril and the O of the black pupil. The top of her head is C-shaped while the way he wrote S’s in his signatures (center) resemble the curves of her claws.4

Just as in a picture of a studio a painter and model must both represent the artist, so must the cat and bird. You can see that in the eye-shape of the bird's torso and its vaginal resemblance too (bottom). As an eye, it probably refers to the winged eye of Picasso's imagination and his chosen namesake, the winged Pegasus or Pegaso in Spanish5. The ‘eye’ also honors, as Picasso so often did, the two great masters who inspired him most: Velazquez in the V of the bird's beak and M's for Manet in the feathers around it. A winged eye was also the monogram of the first art theorist of the Renaissance. As for the vagina, wait and see.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Fur often suggests the bristles of a paintbrush. That's why the cat’s tail is straight as a brush and points to the edge. In self-portraiture a hand near the frame implies the picture's surface is a mirror. To make such a portrait the Renaissance artist faced his canvas while turning to check his features in a mirror to one side, just as the cat/Picasso in her/his 'self-portrait' turns towards us. That meant the brush-hand would appear close to the left or right edge just as the cat's tail does.6

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Picasso's Cat Catching a Bird (1939)

Lower L: Detail of Picasso's Guernica (1937)

Lower R: Detail of Manet's Olympia (1863)

Click image to enlarge.

Two years before, the bull in Guernica was 'Picasso', its head turned similarly (bottom). And its tail, close to the edge, 'paints' on a canvas-shaped wall so that it becomes both 'brush' and 'painting' as the tail is in our picture too.

The cat also derives from Manet's in Olympia (below right) whose first three legs from the left form M for Manet just as Picasso's name is in his cat.7 Manet's, alert on a courtesan's bed, was scandalous in its day for sexual connotations. Ours with an erect tail is sexual too. The French always use le chat for a female cat even though it ought to be la chatte. Why? La chatte is a vulgar word for vagina so Picasso implies his vaginal cat 'paints' itself as a vaginal bird, both giving birth to visual ideas. And just as the artistic mind at its best is androgynous so is the female cat with a phallic tail.8 And now for the real surprise......

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Detail and diagram of Picasso's Cat Catching a Bird

Bottom: Illustration of draughtsman in similar position

Click image to enlarge.

A short, black curve on the cat's torso just after the right-hand stripe is an eye on the head of a craftsman using his right arm to draw while the left supports his weight. The photo below should help you see it. That's why the cream-colored line under the cat's far leg extends beyond it to suggest that it is also the paper on which the artist draws. Now see how the near claws resemble fingers.

Most of Picasso's finished works as an adult we have seen, and many in childhood, use self-references to art and art-making as canonical art always has done. They depict the artist's own mind at the moment of the art's creation when mind and hand, long trained, are at one with each other and nature. The scene, as in all art, can help us recognize our own potential by suggesting that we all 'paint' our own reality as a reflection of ourself. And to change it, we must change ourself. How wondrous, though, that Picasso, in being so traditional, constricted and conservative, looks original.

(Written by Adam Brown and Simon Abrahams)

More Works by Picasso

Picasso kills a bull with his own paintbrush while indicating his divinity.

Picasso’s Bullfight Scene (1955)

Notes:

1. See the theme explained in Artist as Animal.

2. Ibid. in Insight-Outsight

3. Ibid. in Conception (Sexual and Mental)

4. Ibid. in Letters in Art

5. See "Picasso's Parade and His Mysterious Name" (2011)

6. For further explanation, see “Pointing to the Edge” (2012)

7. Manet's Olympia is even constructed similarly to Picasso's Cat Catching a Bird. They both have two principal figures, an alter ego of the artist who 'paints' a figurative representation of his own self as something else. See "Manet's Olympia: Part One".

8. See the theme explained in Androgyny

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 14 Mar 2016. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.