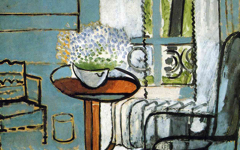

Matisse’s Still-Life with Dance (1909)

Matisse, Still-life with "Dance" (1909) Oil on canvas. Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Click image to enlarge.

In this 1909 "still-life" Matisse included a recent painting in the background, Dance I, now at MoMA, New York. Here at upper left it includes the detail of outstretched hands based on Michelangelo's Creation of Adam. Historians have consequently concluded that Matisse's theme is the creation of life and note that there are both real and "painted" fruit on the table. The flowers also link the foreground to the painting behind.1 These are good observations but what's the purpose? To know that, we must see more.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top L: Matisse's Still-Life with "Dance" (1909)

Top R and below: Photographs of Matisse in his studio (1909)

Click image to enlarge.

For starters, the table is not really a table. It is Matisse's "palette" held close to his body which is why it looms so large in the foreground. We see it from his viewpoint; his palette has become a table. In both photos at left Matisse's rectangular palette becomes a parallelogram, the same form as the "table". For artists, it is a natural metaphor. In Italian the word for palette literally means a small table which is, in reality, what Picasso always used for a palette too.2 The pink cloth is key as well, substituting for the piece of fabric painters use to wipe away paint or rub it in, a common but unseen motif throughout centuries of art history.3

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Deatil of Matisse's Still-Life with "Dance"

Bottom L: Diagram of detail above

Bottom R: Detail of Matisse's Still-life with "Dance" with, inset, the signature rotated and enlarged

Click image to enlarge.

As if to drive home that what we see is not his real studio but the one at work inside his head, Matisse arranged the stretchers leaning against the wall to form the first three letters of his name, as can be seen in the diagram at lower left: an M (green), half an A (red, the other half obscured by the canvas) and a T (orange) in the style of his signature (right, inset), the crossbar on only one side of the upright. It is inverted like the other two symmetrical letters because the scene itself is the mirror-surface of his mind.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top L: Detail of Matisse's Still-life with "Dance" (1909)

Bottom L: Diagram of above detail

R, above and below: Photograph of Matisse in Munich (1910)

Click image to enlarge.

To date I have shown how Matisse's self-portrait is hidden in six works; this one is no exception. First compare the diagram below to the contemporaneous photograph on the right and you should see the tip of his nose and nostrils in the top of the vase, the curve of his moustache in its handles and his eyes and eyebrows in the flowers. His eye on the left is actually the black hair of the dancer in the painting behind. However, within its quote from the Sistine Chapel, she is Michelangelo's God which means Matisse's eye is both divine and, in some sense, Michelangelo's too, one artist's eye as another. Besides, I will soon show in its own entry that the drop-shaped hair of the dancer symbolizes a paintbrush. As Matisse's "eye" though, being solid black, it suggests darkness. In contrast the other pupil is only a small dot. Thus, as so often, one eye of the artist is open for exterior perception, the other closed for insight.

Click next thumbnail to continue

With veiled self-portraits like this - I have now published nearly 100 - a painting does not represent exterior reality but the inside of the artist's mind where, naturally, her or his self-image abounds. Still-life with "Dance", like so many masterpieces, demonstrates in part how human perception is a function of imagination and thus how thinking determines life, at least our view of it. Indeed our imagination is so powerful it alone can increase happiness and ease life's sorrows. Artists know that because they were experts on the mind and consciousness long before Freud. Like prophets they tell us what we need to know if we will but listen. And they, it appears, have long believed that their own creative force is the same one that brought you into being which is why they do not think it theirs, personally. We all have it; they just make better use of it. In brief, since we are all created with creative powers, artists use metaphors of their own craft to show how, by using our imaginations, we too can turn ourselves into a masterpiece.

More Works by Matisse

See how Matisse himself appears in even a simple drawing of an unidentified model

Matisse’s Seated Young Woman in a Patterned Dress (1939)

Notes:

Notes to be completed soon

1. Jack Flam, Matisse: The Man and His Art, 1869-1918 (London: Thames & Hudson) 1986, pp. 271-2

2. Françoise Gilot and Carleton Lake, Life with Picasso (London: Thomas Nelson & Sons) 1965, p. 110

3. See.....

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 15 May 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.