Picasso’s Woman with Clasped Hands (1907)

Treat titles with extreme caution. We rarely know who conceived them, the artist (seldom) or the museum curator and academic (often). In either case they immediately inhibit the imagination, closing down avenues that you otherwise might explore. Once the viewer reads the title of this painting as Woman with Clasped Hands, a study for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, how many will see the figure as a man? As Gaile Ann Haessly has written of androgyny in Picasso's work, he was always "interested in double readings for single images" and in figures like this one created a dimorphic sign, a double arc reading as both female breasts and male pectorals.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

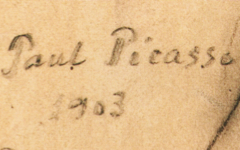

L: Detail of Picasso's Woman with Clasped Hands (1907)

R: Photograph of Picasso at the Bateau-Lavoir (c. 1908-9)

Click image to enlarge.

Even discussions of style can shut down other readings. Once this "woman" is described as proto-cubist because of the deformation of her head, diagonally sliced off, you might not see the diagonal line of Picasso's own hairstyle. This woman, an androgynous precursor of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, is Picasso.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Detail of Picasso's Woman with Clasped Hands (1907)

R: Detail of Picasso's Self-portrait (1907)

Click image to enlarge.

And as for her eyes, they are not an oddity of style either but triggers of meaning. One is open to the exterior world while the other, darker, looks within. Picasso differentiates his eyes because the fusion of our inner and outer worlds leads to unity. Her ear, quite prominent, is also like the large one in Picasso's contemporaneous Self-portrait (right).

Click next thumbnail to continue

The trouble is our minds are naturally lazy. Once we name something, we forget to look beyond the definition which is why, in part, so many viewers are bored. You can, though, spice up your enjoyment of art by taking all titles with a pinch of salt. Think differently.

More Works by Picasso

See how Picasso writes his own identity over someone else's face

Picasso’s YO’s in Piero Crommelynck (1966-71)

Notes:

1. Gaile Ann Haessly, Picasso and Androgyny: From Symbolism Through Surrealism, PhD Diss., Syracuse University, 1983, pp. 6, 134, 273.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 28 Feb 2015. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.