Mengs’ Christ on the Cross (1761-9), Goya’s and Francis Bacon’s too

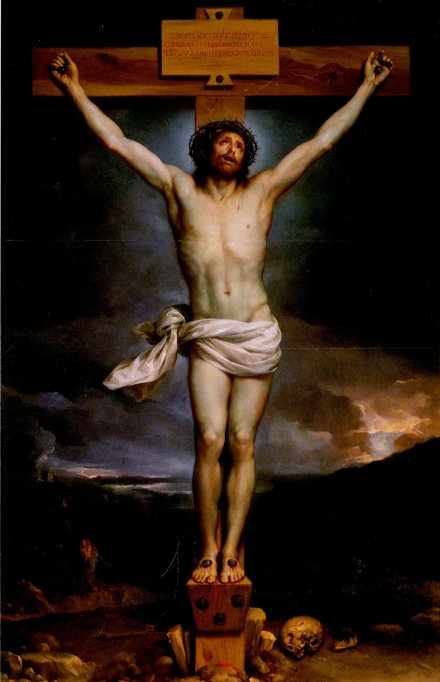

Mengs, Christ on the Cross (1761-9) Oil on panel. 198 x115 cm. Palacio Real, Aranjuez

Click image to enlarge.

Anton Raphael Mengs' painting of the Crucifixion is not well-known but a good example of art's hidden allegory. Far in the distance lightning strikes a hill while the sun sets. In the foreground darkness has descended further, the day has passed and the light on Jesus comes from.... Where does it come from? And why is there an eye-shaped oval in the sky?...

...Once again, as so often in truly poetic art, the scene is inside the artist's own head, behind his eye.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Diagram of Mengs' Christ on the Cross

R: Mengs, Christ on the Cross (1761-9)

Click image to enlarge.

That explains the oval. The light in the distance is the light outside the eye. Christ on the Cross is inside Mengs' head in the world of ideas. The Crucifixion was at that time painting's iconic subject. Mengs, like other artists before him and since, has imagined his own creative moment as mystical, his creative struggle as Christ-like and the painting's execution (an intentional pun) as excruciatingly painful.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

Mengs has conceived his painting as a fusion of his subject's real or fictive location with his own actual presence in the studio. The light on Christ (divine light on one level) resembles studio light flooding in from large windows behind the artist while the wooden Cross, constructed with large nails like those through Christ's feet, suggests an easel with "Christ" as a painting resting on the easel's ledge. An inscribed panel above Christ's head strengthens this suggestion while the skull and bones nearby are studio props like the plaster casts of human anatomy so often used by artists.2 The skull also suggests that man must look inwards for truth.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Goya's androgyne Christ also stands on a wooden ledge as though he is a painting on an easel. Without background, Christ stands in the darkness of Goya's mind with much the same meaning as the Mengs'.

More recently Francis Bacon painted scenes of the Crucifixion which a Bacon specialist, calls "the archetypal image." He also argues that the Cross becomes in Bacon's painting a literal and metaphorical "armature."3 (An armature is to sculpture what an easel is to painting.) Thus Bacon's Christ (deformed à la Bacon) is coming-into-being as "a sculpture", a "work of art" or "a painting." On the universal level of art, the level on which painting becomes art, change comes slowly.

Learn how one scene can turn into another through visual metamorphosis

Bacon’s Two Men Working in a Field (1971)

Recommended Resources

Notes:

1. Searching for further wisdom in word-play an archetypal pain is excruciating if it is, etymologically speaking, out-of-the-cross.

2. For another example of paintings in which skeletal remains on the ground imply their presence in the studio, see Abrahams, "Carpaccio's Dragon's Blood",

3. Andrew R. Lee, "Francis Bacon, Medievalist?" in Francis Bacon: New Studies, ed. Martin Harrison (Göttingen: Steidl) 2009, p. 186, 188-94

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 06 Jun 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.