Picasso’s Parade (1917) and His Mysterious Name

Artists' names are important. They probably always have been. Dante's interest in the significance of names would once have been well-known, especially his habit of referring to characters through part of their anatomy. Vasari, the first modern art historian, also played on their names in compiling his biographies. Painters as varied as Michelangelo, Titian, Rubens, Courbet and Cézanne had all punned on their names in their compositions.1 Yet no-one was thinking of this when in 1881 José Ruiz y Blasco and his wife, Maria, named their son. Known throughout his childhood and adolescence as Pablo Ruiz, the young artist tried out variations of his name on both paper and canvas (some survive) before choosing in his early twenties to be known as Picasso, his mother's family name, a choice which greatly upset his father's family.2 His Ruiz uncle had even helped him get through art school. Why would he do that? There had to be an important reason.

Jaime Sabartès, Picasso's secretary (left), always claimed that the painter was embarrassed to have needed financial help and held his uncle's charity against him. According to the biographer John Richardson, by some accounts a snob himself, "the 'poor relation' syndrome exacerbated Pablo's resentment even further, until the pompous, pious uncle came to stand for everything the nephew loathed about Malaga - provincial hypocrisy, snobbery, stinginess."3 Yet Richardson is inconsistent. A few pages later, he declares that it was Picasso's snobbery not his family's which determined the name though he adds superstition to the mix to make his argument seem stronger.

Click next thumbnail to continue

"The truth is surely", Richardson writes, "that the loyal Sabartès (left) was unwilling to admit that Ruiz was as common a name as any in Spain and, by virtue..[of being his father's] one that connoted failure. To someone as superstitious as Picasso, this would have been a bad omen. A change had to be made."4 Although the rich uncle continued to urge his nephew to sign his art "Ruiz", he became from that moment on the "Picasso" we know.

We will return to the name in a moment. For now, let us turn to his art.

Click next thumbnail to continue

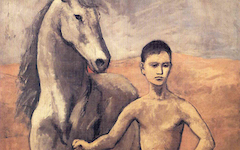

In 1917 Picasso designed the costume and sets for Parade, a Diaghlev ballet. He also painted the so-called red curtain with a scene the audience could focus on during the preliminary overture. According to Richardson, Picasso wanted it to portray backstage as if it was onstage.5 This is highly significant. Many paintings interpreted on this website, including all of Manet's great masterpieces, are depictions of artists "backstage" (the studio) as though they were "onstage" (in the painting.) This is not coincidence.

Click next thumbnail to continue

With time short and his assistant late, Picasso began work on the curtain himself climbing "up and down a very tall ladder similar to the one in the curtain." The seated sailor with raised arm is also said to resemble Picasso's tardy scene painter which may explain why he sits in front of what resembles a painting, his head turned over his shoulder as painters often do in their self-portraits.6 The woman behind him is in the studio (see her legs) while also seeming to be in the painting behind her (see torso and head).

Click next thumbnail to continue

Most importantly the winged horse Pegasus, who later reappears in sketches for Guernica and on the walls of Picasso's chapel in Vallauris, represents the artist though only one writer to my knowledge has ever noted this and the hidden pun. Even he does not understand its significance.7 Pegasus in Spanish is Pegaso. Thus Pegaso is Picasso. The horse, off-spring of the Gorgon Medusa and friend of the Muses, long symbolized the source of poetic inspiration. Picasso may indeed sound more exotic than Ruiz but Picasso's real reason for choosing Picasso was its homonymic link to Pegaso. It is revealing of art history's mistaken paradigm that no-one has ever noted this before. Once known, the whole meaning of the curtain changes, as does Guernica and Picasso's art in general.

See conclusion below

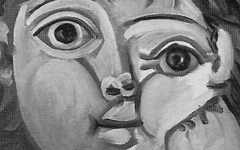

Cognitive psychologists have long known that a fondness for puns and creative insight in all fields, from science to art, are closely linked. It is a sign of homospatial thinking, the ability to superimpose or fuse seemingly unrelated ideas.8 It separates original thinkers from merely logical ones. Without that ability great masters could not express one meaning in a work of art for their patron and public and another for themselves and other artists, nor could they recognize nor produce metamorphic form. Durer’s comment about seeing the likeness in unlike things is symptomatic of all creative thinkers, a thought process also present in Michelangelo’s notion about sculpture. Good sculptors, he wrote, see the future work pre-existing in the stone, one image laid on another. Picasso saw something similar in Pegaso.

More Works by Picasso

Notes:

1. Michelangelo used the Archangel Michael to represent himself holding up God in the Creation of Adam; Titian signed his name on the breast of a woman to connect Tiziano with ‘titta’; Rubens painted a reddish landscape to reflect his name (rubens= reddish); Courbet depicted the figures in The Stonebreakers bent (courbé) to rhyme with his name; Cézanne emphasized a figure's shoulder (épaule) to draw attention to his name (Paul)

2. John Richardson, A Life of Picasso, 1881-1906, vol. 1 (New York: Random House) 1991, p. 106

3. Wiliam F. Buckley, Jr., "Who's he?" (Review of Joseph Epstein's Snobbery: The American Version), The New Criterion 21, September 2002, p. 67

4. Richardson, op. cit., p. 106

5. Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932, vol. 2 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) 2007, p. 37

6. Richardson 2007, p. 36

7. Josep Palau i Fabre, Picasso: From the Ballets to Drama (1917-1926), trans. Richard Lewis Rees (Hagen, Germany: Konemann) 1999, p. 48 cited in Richardson 2007, p. 37

8. Roy Dreistadt, “An Analysis of the Use of Analogies and Metaphors in Science”, The Journal of Psychology 68, 1968, pp.97-116; Albert Rothenberg, The Emerging Goddess: The Creative Process in Art, Science, and Other Fields (The University of Chicago Press) 1979, pp. 71, 75, 117-8; Rothenberg, “Artistic Creation As Stimulated by Superimposed Versus Combined-Composite Visual Images”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39, 1980, pp.370-81; R. Ochse, Before the Gates of Excellence: The determinants of creative genius (Cambridge University Press) 1990, p. 215; Dean Keith Simonton, Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity (Oxford University Press) 1999, p. 30

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 27 May 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.