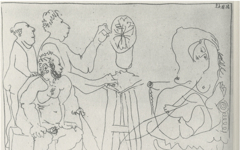

Picasso’s Portrait of Gongora (1947)

Left: Picasso, Portrait of Góngora (1947)

Right: Velazquez, Portrait of Luis de Góngora (1622)

Click image to enlarge.

In 1947 Picasso illustrated a book of Góngora's poems. He wrote the lines himself in pen and ink which he then embellished with engraved marginalia. The portrait (far left) adorns the first poem called "To an Excellent Foreign Painter Doing My Portrait." What, though, does Picasso's portrait mean beyond the fact that it is a variation on Velazquez's original (near left). I have already shown, somewhat surprisingly, that the latter includes a female breast near Góngora's temple and is thus an image of creation in Velazquez's mind?1

Click next thumbnail to continue

Picasso, Portrait of Luis de Góngora, according to Velazquez (27th February 1947) Lithograph

Click image to enlarge.

In his own act of magic Picasso changed Góngora's facial features while maintaining his likeness. Góngora's nearly invisible eyebrows are now big and black with one like a teardrop; his upper lip, asymetrical in the original but largely straight, zig-zags like the teeth of a saw or the initial M for Manet. I mention this because Picasso's devotion to Góngora was like Manet's for Edgar Allan Poe. Poe's poems and likeness Manet also commemorated in monochromatic prints. Picasso's interest in Manet then, though well-known, may have been longer and more profound than any art historian has yet imagined.2

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Picasso, Portrait of Luis de Góngora, according to Velazquez

Right: Diagram of Picasso's Portrait of Luis de Góngora

Click image to enlarge.

Although Góngora's lapels are indecipherably dark in reproduction, they become in Picasso's variation arched eyelids framing his deep black pupils, a noted feature of Picasso's face. Above Picasso's "eyes" sits the great Spanish poet in the center of Picasso's "mind" like Dante's in Michelangelo's in the Last Judgment.3 That also explains why the poet's lips would spell the letter M for Manet.4 Picasso's "poet" is a combination of Picasso's muses, not Góngora alone.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Góngora was known for the depth and multiplicity of his metaphors letting "common objects take on multiple existences."5 No wonder both Velazquez and Picasso admired his poetry. Picasso even published a second variation on the portrait independently of the book. Here the lapels look even more like "eyes". Like Velazquez, Picasso then placed his other metaphor above the eye-line of Góngora's head. It is unseen as well. Remarkably, even though Góngora did not have a lock of hair in the center of his forehead (who does?), no-one I have ever read has noted it. Yet that big, black comma is clearly Picasso's addition. Why?

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Picasso's Portrait of Luis Góngora, rotated.

Right: Diagram of sleeping baby in detail at left.

Click image to enlarge.

In adding that mark Picasso delineated an infant's "closed eye" and thereby magically turned the poet's bald pate into the "head of a sleeping baby". The poet's frown is the child's "button nose". There are now two ways to view this print. You can either see a Picasso-like portrait of Góngora, his baldness radically altered by Picasso for no reason whatsoever or you can imagine that Picasso has depicted the Spanish poet's mind (and thus his own) as a dreaming child, pure and God-like. I leave you to decide which is more poetic - and thus more likely.

More Works by Picasso

Notes:

1. In an entry titled Velazquez's Portrait of Luis de Góngora (1622)... (30 May 2012) I demonstrate how to see the breast in the poet's head with a clearly delineated nipple above his ear.

2. Picasso's references to Manet in his art range from visual metamorphoses of Manet's compositions, many already recognized, to metamorphic compositions of Manet's name and signature, the latter still virtually unknown. I will be adding examples to the site whenever possible.

3. For an explanation of how to see Dante's head in the Last Judgment and of its meaning too, see the entry A Quick Guide to the Sistine Chapel (16 Feb 2011).

4. Manet himself used "M" shapes to spread his initial across his works. For one example among many, see Manet's Monet Painting on his Studio Boat (1874).

5. Edward Hirsch, "Preface" in Góngora: Poems by Luis de Góngora y Argote (New York: George Braziller) 2007, p. 2

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 04 Jun 2012. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.