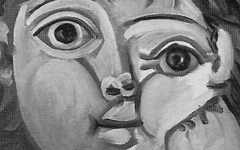

Picasso’s Standing Female Nude (1910)

Most discussions of a Cubist drawing center on the originality of its style, its challenge to visual perception or its reception by contemporary critics. Of the latter, one well-known comment is Alfred Steiglitz’s self-serving observation that this example “was probably the finest Picasso drawing in existence.”1 He owned it. To be worth your time, though, we need to show you something new, something that no writer has ever seen before. I say “writer” because there is almost nothing that some artist has not seen before. Artists can see what others don’t.

Picasso, Standing Female Nude (1910) Charcoal on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Click image to enlarge.

Picasso almost always signed his drawings. Of those exhibited in major exhibitions the vast majority are signed on the front or, if he felt it would interfere with the image, on the reverse. Of those without an obvious authorial mark at all, many are Cubist. Picasso said that cubism “so deeply bore his mark that at its height he had not even felt the need to sign it.”2 No wonder.

Even though this drawing may summarily suggest a standing nude, it is not just made out of signs for arms and legs but the letters of the alphabet. Take a look at the next diagram.

Click next thumbnail to continue

There are at least six P’s all designed in the various lollipop-ways Picasso wrote the P of his signature, a stick with a square or roundish form on top. There are also five I’s, six C’s, three A’s, one S and many circular lines suggesting an O including the nude's head. Since the mind is like a mirror, it is not surprising that some of the letters are inverted. Nor does it matter whether all the letters are there; to Picasso they meant PICASSO.3

Click next thumbnail to continue

This is an image of Picasso’s androgynous mind in the process of conceiving a "female" nude though, made from the letters of his name, she too is androgynous. As a mental image, the nude is seen from different perspectives because that is the nature of mental images. Most of us are unaware of mental images in our minds; some artists, though, can see them. Mozart, for instance, could “survey it [a composition], like a fine picture or beautiful statue, at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them, as it were, all at once.”4 Like the multiple perspectives of a Cubist drawing?

See conclusion below

Mozart's observation must be accurate because Beethoven described his mental image of his music in exactly the same terms: “...In my head, I begin to elaborate the work in its breadth, its narrowness, its height, and its depth, and as I am aware of what I want to do, the underlying idea never deserts me. It rides, it grows up. I hear and see the image in front of me from every angle, as if it had been cast...” [italics added].5 Picasso who once expressed surprise that the mental image of a work and the finished painting do not differ very much probably knew that the painting in question was a mental image. Picasso even described what a mental image looks like and it sounds like Cubism:

‘If we think of an object, let us say a violin, it does not appear before the eye of our mind as we would see it with our bodily eyes. We can, and in fact do, think of its various aspects at the same time. Some of them stand out so clearly that we feel we can touch and handle them; others are somehow blurred. And yet this strange medley of images represents more of the ‘real’ violin than any single snapshot or meticulous painting could ever contain (italics added).’6

More Works by Picasso

Notes:

1. Picasso's Drawings, 1890-1921 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2011, p. 192

2. Rosalind Krauss, The Picasso Papers (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 1998, p. 202

3. I have already shown how Picasso used the letters of his name to construct several non-Cubist paintings (see Letters in Art)

4.“Mozart: A Letter” in Brewster Ghiselin, The Creative Process (New York: The New American Library) 1952, p.45

5. M. Hamburger, Beethoven: Letters, Journals and Conversations (New York: Pantheon Books) 1952, p. 195; also cited in Albert Rothenberg, “Homospatial Thinking in Creativity”, Archives of General Psychiatry 33, 1976, p. 20

6. Paul Smith, Interpreting Cézanne (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang) 1996, p. 73

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 29 Oct 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.