Titian’s Mary Magdalene(s) (c.1530-60)

Colin Eisler writes of Titian's various versions of the Magdalene: "Mary Magdalene affords the faithful, lustful, or both a legitimate occasion to see a beautiful penitent wearing little but her long tresses, looking very well indeed as she does good by renouncing the bad.....Almost as erotic as the Mary Magdalene is...."1 The idea that Titian used his brushes, his colors, his mind and months of meditation on a 3-foot x 4-foot piece of very expensive soft pornography is, to be kind about it, shallow. Titian painted a string of pictures devoted to the Mary Magdalene, a sustained meditation on one of Christianity's most important symbols. Mary was the first to see the Risen Christ, thus announcing his Resurrection to the world, and was apocryphally believed to have also been present at the Last Supper. She also saw the Entombment, at least she did in Titian's Pieta and many Crucifixion scenes by other artists. Thus Mary was one of the last to see Jesus at death and the first to witness his re-birth. Although few Gnostic gospels were available in the Renaissance, gnostic wisdom appears to have been handed down orally and pictorally from one practitioner to the next and from one work of art to the next. There should be no doubt that Gnostic knowledge colored the spiritual knowledge of numerous Renaissance artists as it did their paintings too.

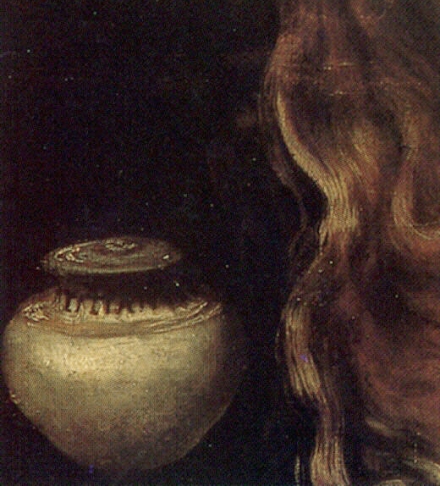

Titian, Penitent Mary Magdalene (1531) Oil on canvas. Palazzo Pitti, Florence

Click image to enlarge.

In the Gospel of Thomas Jesus announces that he will make the Mary Magdalene male "so that she also may become a living spirit like you males. For every woman who has become male will enter into the kingdom of heaven."2That piece of esoteric wisdom strongly urges Christian practitioners to become mentally androgynous. Without that androgynous perspective, no human of either gender can purify their soul to enter heaven3. Mary, we will soon see, is "Titian" painting himself as "a work of art". Fortunately, eminent art historians already accept the fact that Renaissance artists thought of female beauty as a synechdoche for the art of painting itself.4

Click next thumbnail to continue

Rona Goffen demonstrated how Titian had a special sense of identification with Mary Magdalene, even writing letters to his patrons as though the saint was his personal envoy and intercessor.5 She was, in "fact", Christ's female confidante libelled by misogynists in the Secular Church as a sinner-saint, her supposed harlotry an additional way to make women seem sinful. In this painting Titian links the hairs of her tresses with the hairs of a paintbrush, her hands placed flat on her torso like the painter "painting" himself. The jar of ointment, traditionally linked with a paint-pot, is even inscribed with Titian's name implying that her cosmetics was his paint.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Mary makes the same gesture, her hand facing outwards, in one of Titian's last paintings, the Pietà painted for his own tomb. In it she seems to call for help when, on the level of poetry, her raised hand is in fact placed flat on the surface of the invisible mirror, the "canvas" itself and the mirror of Titian's mind. Inside the "painting" Titian is on his knees as Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea, two mythic sculptors thought to have been present at Christ's burial. Not known is that Titian as a "saintly" artist here uses his beard as a brush to metaphorically paint the Virgin and dead Christ. They are the Pietà, a work of art, which is itself based for that reason on Michelangelo's celebrated Pietà. This also suggests that, despite their rivalry, great artists feel that they share the same or similar soul.

Click next thumbnail to continue

In another version of the Mary Magdalene, painted in 1567-8 thirty years after the first one, Titian continues to identify with the Magdalene. In it, he retains the same hand gesture with his name inscribed above the pot rather than on it. Titian's self-representation in this work is supported by Goffen who concluded that all Titian's portraits of the Magdalene are "in some sense self-portraits." I even believe - it's just a hunch based on experience - that Titian has formed the trees and vegetation hanging over the cliff.....

Click next thumbnail to continue

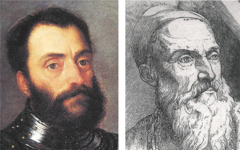

Top: Detail of Titian's Mary Magdalene (1567) compared to a detail of Titian's 1567 Self-portrait, inverted

Bottom: Diagram of Titian's Mary Magdalene (1567) compared to a detail of Titian's 1567 Self-portrait, inverted

Click image to enlarge.

........into his own profile as seen in a self-portrait painted the same year. Its position on the hill implies that everything in darkness behind Titian's facial "contour", including the figure of the saint, is inside Titian's mind.6

Titian's sense of identification with the women in his paintings, although revealed by Goffen in the 1990's, is still not widely enough acknowledged by art scholars as an important part of Titian's meaning which is itself of spiritual importance. The idea that Titian's nudes are just a form of soft pornography must be rejected.7

More Works by Titian

Notes:

1. Eisler, Paintings in the Hermitage (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang) 1990, p. 291

2. Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass, “Fetishizing Gender: Constructing the Hermaphrodite in Renaissance Europe” in Body Guards: The Cultural Politics of Gender Ambiguity, eds. J. Epstein and K. Straub (New York and London: Routledge) 1991, p. 85

3. The idea of heaven as an exterior place in the sky where we might go after death is an early metaphor for the purification of the individual soul and its unity with the divine. The Church has, however, used the promise of heaven to appeal to lay people without the capacity for spiritual development. "Heaven", though, is code in spiritual works for the individual's attainment of his or her own spiritual goal; it is not a residence in the clouds nor a post-mortem retreat.

4. Elizabeth Cropper, “The Beauty of Woman: Problems in the Rhetoric of Renaissance Portraiture” in Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe, eds. M.W.Ferguson, M. Quilligan and N.J.Vickers (University of Chicago Press) 1986, p. 176; Rona Goffen, Titian’s Women (New Haven: Yale University Press) 1997, p. 28

5. Goffen, op. cit. , pp. 8-11, 178, 185.; Titian's identification with the Mary Magdalene is by no means unique among men. See Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, Jesus and the Goddess: The Secret Teachings of the Original Christians (London: Thorsons) 2002, p. 148

6. Titian made the branches of another tree form his own self-portrait in the Venus and Cupid with a Partridge (c.1550) in the Uffizi, as I will soon explain.

7. It is worth noting that even St. Jerome (c.347-40 - 420) identified himself with Mary Magdalene in texts that Titian might well have known. See Zbynek Smetana, Titian's Mirror: Self-portrait and Self-Image in the Late Works, PhD Diss., Rutgers University, NJ 1997, pp. 175-6

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 08 Apr 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.