Titian’s Ambassador Portrait (1541-2)

Titian's portrait of a man who was, years later, to become the ambassador to the Ottoman Porte, Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramont, is always thought to be an important historical document. He eventually became a fascinating figure who encouraged early scientists, spent many years at the Ottoman Court and witnessed important battles on land and sea. But, from our perspective as art lovers, so what? Besides, in 1541, Titian would have known nothing of all that.

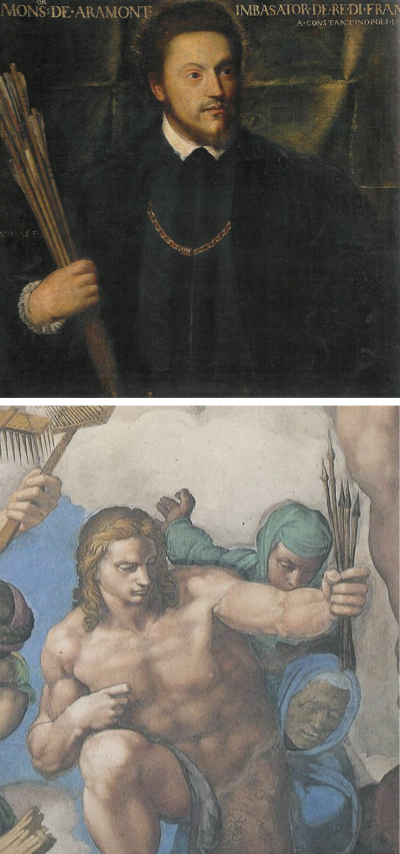

Titian, Portrait of Ambassador to the Ottoman Porte Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramont (1541-2)

Click image to enlarge.

Those who emphasize the sitter's biography in describing portraits are focusing on issues that may have been entirely peripheral to the artist's thinking. Titian did not think of himself as a journalist because even factual accounts of history at that time were in their infancy. Accuracy, regardless of the patron's wishes, was not his goal. Titian, like other artists, was a visual poet and he painted poetry not "photographs." He always followed, whatever the commission, the most important poetic principle of significant art, that every painter paints himself. How did he do that here?

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Titian's Portrait of Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramont

Right: After Titian, Detail of a lost self-portrait (inverted)

Click image to enlarge.

Titian was over 50 years old when he started the portrait and the Ambassador looks so like a copy of one of Titian's lost self-portraits (painted probably around the same time) that the portrait can hardly be a good likeness of the Ambassador. Gabriel de Leutz, it now seems, has become an alter ego of the artist.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Titian, Portrait of Ambassador to the Ottoman Porte Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramont (1541-2)

Click image to enlarge.

The ambassador stands, moreover, before some hanging fabric bearing a strong resemblance to canvas. He also holds a fistful of arrows which we have shown elsewhere were a common symbol for paintbrushes in part because of their similar shape. Since Titian also began this portrait the same year Michelangelo unveiled the Last Judgment the portrait's similarity to Michelangelo's St. Sebastian holding a fistful of arrows as paintbrushes may not be coincidental. (See separate entry.) Titian so admired Michelangelo that he later included a version of the sculptor's Vatican Pieta in the painting intended for his own tomb.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Titian's Portrait of Ambassador Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramont

Right: Detail of Britto's engraving of a lost Titian self-portrait

Click image to enlarge.

Lastly, the gold chain around the Ambassador's neck was the symbol of a ruler's favor, a mark of respect. It was a high honor that Titian proudly displays in his own self-portrait (near left). Chains like these in art symbolized an artist's mastery and were used by El Greco, Rubens, Van Dyck, Velazquez and others for the same purpose: as the sign on an alter ego of a great master.

See conclusion below

In positioning the ambassador in front of the canvas-like cloth Titian suggests that his sitter is both the artist (holding his brushes) and the subject, thereby fusing the picture's subject with its own making and implying, as ever, that every painter paints himself. He turned what was probably a dull commission into visual poetry though, sad to say, this has only ever been seen by other artists.

More Works by Titian

Notes:

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 19 Feb 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.