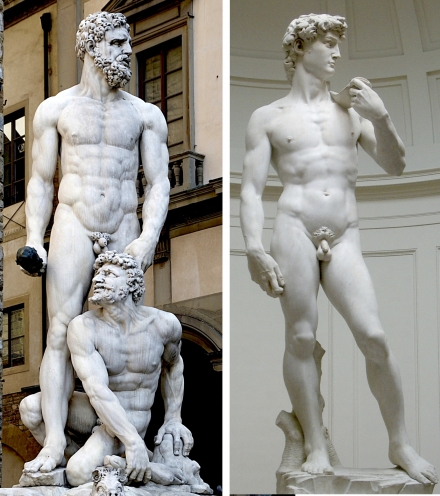

Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus (1525-34)

Bandinelli, Hercules and Cacus (1525-34) Marble. Piazza della Signoria, Florence.

Click image to enlarge.

Baccio Bandinelli admired and competed with the older Michelangelo all his life but never escaped the great man's shadow. When the Republican government of Florence decided to order Hercules and Cacus as a companion piece for David at the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria, they originally gave the commission to Michelangelo. A decade later, after a change of government, the marble ended up in Bandinelli's hands. This, then, is the story of what he sculpted.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Detail of Hercules' face in Bandinelli's Hercules and Cacus (1525-34)

Bottom: Detail of Bandinelli's Self-portrait (1555-7)

Click image to enlarge.

Himself. As always, each figure is an alter ego of the artist. Although Bandinelli's Hercules (top) long pre-dates his Self-portrait (bottom), their bearded faces are similar, a "look" Bandinelli used in many figures. This means, as I have suggested of Leonardo and Michelangelo, that the young Bandinelli developed a facial type of what he might look like when old.1 He either was accurate in his prediction or made his later self-portraits conform to that type. His probable purpose, like Leonardo's and Michelangelo's, was to convey his access to wisdom, a concept long symbolized by old age.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Details of Hercules' face (top) and Cacus' (bottom) in Bandinelli's Hercules and Cacus.

Click image to enlarge.

Even Hercules' victim, the kneeling Cacus (bottom), shares Hercules' distinctive hairstyle, the curl to his lower lip and the creases on an artist's forehead. The frown, a very common feature of artists' self-portraits, symbolizes deep thought.2 Even Cacus' beard, with far less growth, is at least curly like Hercules'. Only Cacus' nose is really different and its prominence intentionally persuades the casual viewer to see two different people.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Hercules also resembles his mate, David. Their right arms hang down, both heads turned over the left shoulder, alert and frowning. Their straight, right legs are tensed with toes near the edge of rocky ground with a short, dead tree trunk.3

They stand like sculptors, their heads theoretically looking in the mirror as if making a self-portrait.4 Both right hands (one holds a club) seem ready to strike marble.5 Hercules "sculpts" Cacus while David, one hand turned inwards, "sculpts" himself both as a young hero and giant.6 That may be why Cacus' curly facial hair is only half-alike; it is in the process of being "sculpted" like Hercules'. Cacus is Hercules' "self-portrait" or an alter ego struggling creatively.

Click next thumbnail to continue

The Herculean "sculptor" with Bandinelli's features is depicting himself as his own victim because, in beauty and wisdom (the two are one and the same), all opposites are united. That's why, as EPPH proposes, art has long had one unchanging theme: the creative moment which, understood properly, leads to "heaven" (i.e., spiritual happiness) in this life not the next.

Bandinelli's art is not as awe-inspiring as Michelangelo's but, like many artists and poets, he could see the thematic unity in art unseen by the crowd. And so should we. If not, in the absence of some other method of transcendence, we will forever be hammered by reality.

More Works by Bandinelli

Notes:

1. See Abrahams, "Wisdom and Leonardo's Self-portrait" and Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling: Jeremiah (c.1509-10)

2. See Abrahams, "Art's Unknown Frown" (2013)

3. Almost all of Michelangelo's sculpted figures stand on the edge of creviced rock, a setting also common in the painted religious scenes of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. My own theory is that these rocky foundations are the visual symbol of the brain whose cortex is also deeply creviced. This implies that the figures, standing on top of the (artist's) brain, are an emanation of it or, in other words, a mental image. By the Renaissance stone itself had profound meaning which I also plan to elaborate on at a later date. See "Michelangelo Rocks...." (2013), Filippo Lippi's Adoration in the Forest (c.1460) and "Cubism Explained" (2011).

4. See Abrahams, "Over the Shoulder Poses" (2011)

5. David has a stone in his right hand for the sling which he has not yet used. Clearly Michelangelo as a sculptor of stone identified with David's use of stone.

6. See Michelangelo's David.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 07 Aug 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.