Fouquet’s Charles VII, Bernini’s Richelieu and Rigaud’s Louis XIV

Left: Fouquet, Portrait of Charles VII, detail (c.1450) Louvre, Paris

Right: Fouquet, Self-portrait, detail inverted (c.1450) Louvre, Paris

Click image to enlarge.

An entry on Jean Fouquet's life-size Portrait of Charles VII has already compared the king's face to the artist's own (left). Despite a vast difference in scale the two portraits (ignoring the noses) look remarkably similar and are highly significant. They appear to represent the begining of the long tradition in French art of making France's rulers resemble the artist.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Fouquet, Adoration of the Magi in the Chevalier Hours (c.1455) Illumination. Château de Chantilly, Musée Condé, France

Click image to enlarge.

In a second portrait Fouquet portrayed the king in a Book of Hours as one of the Magi come to adore Christ. Commissioned by the Chancellor of France the book was obviously destined to become an historical icon of great importance. Again Fouquet made ....

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Charles VII as a Magus in Fouquet's Adoration of the Magi in the Chevalier Hours (c. 1455)

Click image to enlarge.

...... the king's face resemble his own: small, tired eyes with similar eyebrows, full lips and a similar chin. The Chancellor, the book's patron, was in a good position to judge the portrait's resemblance to the king. Likeness, though, might have been more malleable in the days before realistic portraits became common. Regardless, whatever the truth, these portraits became the likeness of the French monarch. Picasso's 1905 portrait of Gertrude Stein tells a similar story. It was a poor likeness, the sitter complained, unaware that Picasso had fused his features with hers. No matter, Picasso replied, it will grow to look like you.1

Click next thumbnail to continue

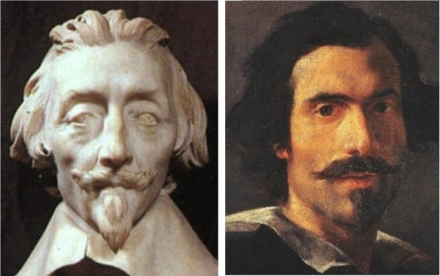

Left: Bernini, Portrait of Cardinal Richelieu, detail (1641)

Right: Bernini, Self-portrait, detail inverted (c.1635) Uffizi, Florence

Click image to enlarge.

The artist as king (or in Bernini's Portrait of Cardinal Richelieu at far left as Chancellor of France) is a symbol of our essential humanity, our soul stripped of its egocentric self to become the king or powerful ruler of all in the sense that our shared humanity is regal. It is part of the mystical message of Christianity and the engine of the creative mind, a level of universal consciousness accessed by artists, mystics and saints but which remains closed to most of us. Nevertheless, if we can think creatively, we too have that king hidden inside us waiting to appear at the birth of Christ in our own mind. (Please note: I am not Christian.)

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Louis XIV in His Coronation Robes, detail (1701)

Right: Rigaud, Self-portrait (1716)

Click image to enlarge.

Hyacinthe Rigaud's definitive portrayal of the most ostentatious French monarch is a puzzle in the same tradition because his self-portrait which all his royal portraits resemble was painted many years later. Perhaps the artist gave himself regal features (the protruding lower lip and cleft chin) and then chose a similar wig. Whatever the truth, the meaning on the poetic level is likely to be similar: the human soul at its most creative is majestic.

Notes:

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 14 Sep 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.