Gauguin’s Self-portrait with a Mandolin (1889) and The Player Schneklud (1894)

Gauguin, Self-portrait with a Mandolin (1889) Oil on canvas. Private Collection

Click image to enlarge.

Gauguin, like many artists from Giorgione onwards, was an amateur musician who played, among other instruments, the mandolin. That does not mean, though, that his self-portrait strumming its strings is a "snapshot". Portraits of the painter - or of anyone - cannot be art if their appeal is restricted to contemporaries. They must have wider meaning that resonates in the visual systems of those not yet born. What Gauguin clearly knew, though, is that musical performance is an age-old metaphor for the making of the art itself. Starting in the fifteenth century, cherubs play instruments at the base of large Venetian altarpieces, often near the artist's signature, to highlight his or her making of the scene.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Veronese, Detail of self-portrait in Marriage at Cana (1563) Oil on canvas. Louvre, Paris

Click image to enlarge.

Not long afterwards Veronese portrays himself with Titian (in white and red respectively) and another painter playing musical instruments in the foreground of The Marriage at Cana, a giant masterpiece in the Louvre. A trinity of poetic painters, they are positioned like cherubs in front of their "painting of Christ." That's why Christ maintains a heiratic pose. He is "a painting". The servants, meanwhile, are the artists' "studio assistants" placing food on the table, filling up glasses and doing other errands to complete the picture. (You can find a fuller interpretation in a separate entry, Veronese's Marriage at Cana.)

Click next thumbnail to continue

Corot, Italian Woman Playing the Mandolin (c.1865-70) Oil on canvas. Sammlung Oskar Reinhart, Winthertur

Click image to enlarge.

Gauguin's immediate inspiration for his self-portrait must have come from two great paintings in the collection of his guardian, Gustave Arosa. He would have been intimately familiar with it. The first, Corot's Italian Woman Playing the Mandolin, seems rather obvious. It is made more interesting by the possibility that Corot positioned the face of the instrument horizontally to resemble a palette. That way the woman both plucks at its strings and "selects paint from her palette". As both model and artist, she sits in Corot's studio as a metaphor for his androgynous mind. In related pictures, Corot's models resembling this one actually paint canvasses on his easel.

Click next thumbnail to continue

The second great painting in the collection was Courbet's The Cellist, now in the Metropolitan Museum. Linda Nochlin wondered in 1963 whether the artist's pose, his torso and hands in particular, might derive from Rembrandt's 1660 Self-Portrait in the Louvre in which the master's hands are in a very similar position, holding brushes, palette and mahlstick.1 She was right without recognizing that the meaning is transferred as well as shape. The long, thin bow is a substitute, after all, for the similarly shaped paintbrush or mahlstick, a link Michael Fried ultimately recognized in 1990.2 Courbet in playing the mandolin imagines himself painting like Rembrandt and Corot.

Click next thumbnail to continue

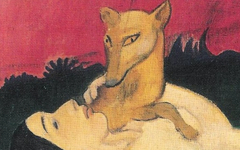

Top Left: Gauguin, Detail of The Player Schnecklud (1894)

Top Right: Gauguin, Detail inverted of Self-portrait of the Artist with an Idol (pre-March 1891)

Bottom: Gauguin, The Player Schneklud (1894)

Click image to enlarge.

In 1894 Gauguin painted a cellist in a portrait known as The Player Schneklud. Without any other portrait of Schneklud, some thought the cellist bore a passing resemblance to Gauguin (top right) and that he might in some sense be a self-portrait.3 It was only in 2000 that a photograph of Schneklud appeared in which he has the same beard and moustache as in the portrait "with a similar strong nose and profile."4 It is therefore a magical and quite typical example of "face fusion" in the modern age.

See conclusion below

Gauguin had found a model who not only had features like his own but who played the cello as well. This allowed Gauguin to create an esoteric image of himself as the spiritual reincarnation of Courbet, Corot and Rembrandt while seeming to simply portray a contemporary cellist. An important aspect of the modern artist's job, then, long overlooked, was the art of choosing a model. It is an issue that has hardly been discussed in the literature; the chosen model, whether a professional one like Manet's Victorine Meurend, or a wealthy one who asks for a portrait, has long been considered a matter of chance. The idea that artists chose their models for their facial or other similarity to themselves - and may have declined to paint others who did not - is an issue that will deserve far more attention in the future.

More Works by Gauguin

What you can see in a self-portrait when you think creatively. Indeed it's your job to become the painter...

Gauguin’s Self-portrait with a Palette (c.1893-4)

Notes:

1. Linda Nochlin, “Gustave Courbet: A Study in Style and Society” (PhD dissertation, New York University, 1963); published New York, 1976, p. 51.

2. Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (University of Chicago Press) 1990, pp. 81-2

3. David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life (New York: Simon & Schuster) 1995, pp. 381-2

4. Stephen Sensbach, "Gauguin's Cellist", Burlington 142, Sept. 2000, pp. 567-70

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 15 May 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.