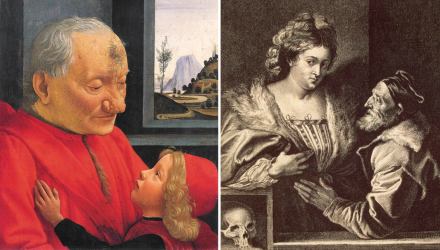

Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of an Old Man and Child (c.1490)

Specialist art historians sometimes recognize in a single work what EPPH shows is common in art generally. Although this painting by Domenico Ghirlandaio is normally described as a memorial portrait of an old man who had passed away with his surviving grandson, John Shearman considered an alternative possibility: that the old man and the boy are on two different levels of reality. “It is probable”, he wrote, “that we should see here an image within the image – that is to say, the boy responding to and demonstrating Ghirlandaio’s skill as a portraitist.” The boy, he inferred, is a spectator “reacting to the image within the image and asserting a triumph of art.”1

Shearman who even noted that the subject of this painting is art could have added that the boy is both the viewer and the artist. He is an alter ego of Ghirlandaio himself in the act of “painting” an old man as the boy's extended arm and the manner of his touch suggest.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Old Man and Boy (c. 1490)

R: Van Dyck (attrib.), Titian and His Mistress (1630's) Engraving.

Click image to enlarge.

A later print depicting Titian makes this clear [see entry].2 The woman's unnaturally large size suggests she too is in a different reality. But see how Titian touches his "painting" in the same way as Ghirlandaio's boy. Although a little-known gesture in art, it was probably instantly understood by artists of the same ilk.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Additional evidence that the man represents a "painting" is in the modeling of the two figures. The man's is flat compared to the boy’s rounded form. He looks flat because paintings really are flat while the boy (an “artist”) is in the space outside. The boy’s hand also faces the canvas, as Ghirlandaio's would have, and since most of his figure is excluded, we can imagine that it is really in the studio.

The artist's craft, perfected through discipline, is represented as a young boy because children, with a less-developed ego than adults, have long represented purer minds, one of the goals in the pursuit of self-knowledge. The artist’s wisdom, on the other hand, is symbolized by the age of the loving "grandfather" who appears to have suffered and, metaphorically, seen everything.

More Works by Ghirlandaio

Notes:

1. John Shearman, Only Connect..... Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance (Princeton University Press) 1992, pp. 108-9 and 147

2. The print is attributed to Anthony Van Dyck and is thought to be after a lost self-portrait by Titian. See Van Dyck's Titian and His Mistress (1630's).

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 29 May 2010. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.