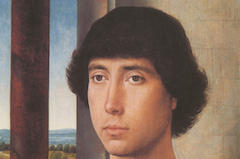

Hans Memling’s Portrait of Tommaso di Folco Portinari (c. 1470)

This early portrait by Hans Memling demonstrates how portraiture, even in the fifteenth century, reflects the artist's own mind. He has not necessarily fused his features with those of his sitter, as you can see many other artists did in the Galleries on Portraiture and in the book, Every Painter Paints Himself . Here Memling uses a different method. It is worth recognizing because many later artists used it as well.

Memling, Portrait of Tommaso di Folco Portinari (c.1470) Oil on wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Click image to enlarge.

Anyone looking at these hands, which are as much the focus of the painting as the face, ought to gain the distinct impression that we are not only looking at two hands praying but also, in a different reality, at one hand touching a mirror. Praying hands often resemble a reflection of each other but here the lighting suggests it too. Since the light comes from the right horizontally, the visible underside of the inner hand should be brightly lit like the outer hand. What we see, instead, is the shaded side of the outer hand reflected in a mirror. This impression is strengthened by the fingers which "touch" each other precisley. There is more, though.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Portrait of Tommaso di Folco Portinari

Right: Diagram of Portrait of Tommaso di Folco Portinari

Click image to enlarge.

Unless there has been substantial repainting, the forearm is most peculiar, coming in horizontally from the left edge of the frame. The elbow, outside the image, is too far from his shoulder. Besides, a forearm connected to a figure facing us would need foreshortening and there is none. (The contour of the sleeve which is difficult to see, perhaps on purpose, is highlighted in the diagram.)

Click next thumbnail to continue

Touching, we reveal on this site, is a symbol on the poetic level for the act of "painting", not only because artists often paint with their fingers but because the moment a brush touches canvas is the moment of creation. Thus this hand, which on the underlying level is the painter's hand touches (thus, paints) the other hand, its own reflection.

See conclusion below

Icon painters prayed before picking up their brush as many medieval artists in the West did too. Painting had long been a sacred act akin to prayer, a reverential conception of the painter's craft that Memling poetically depicts. There are two realities here: the sitter praying and the artist creating the sitter praying who, it turns out, is his own reflection. Memling has painted his alter ego.

More Works by Memling

Notes:

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 22 Oct 2010. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.