John Sloan’s Hairdresser’s Window (1907)

Michael Lobel in the September 2011 issue of the Art Bulletin has revealed how several of John Sloan's New York street scenes of the early twentieth century are, when seen correctly, allegories on the creation of art. Sloan's Hairdresser's Window, now at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, is his prime example.1

A crowd gathers in front of a hairdresser's storefront, some looking up to see her with a customer in the window. Many details, including the name of the hairdresser, are taken from life adding vividness and a reportorial character to the scene. Yet Lobel notes that the hairdresser coloring her customer's hair is like an artist adding paint to canvas.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Detail of Sloan's Hairdresser's Window

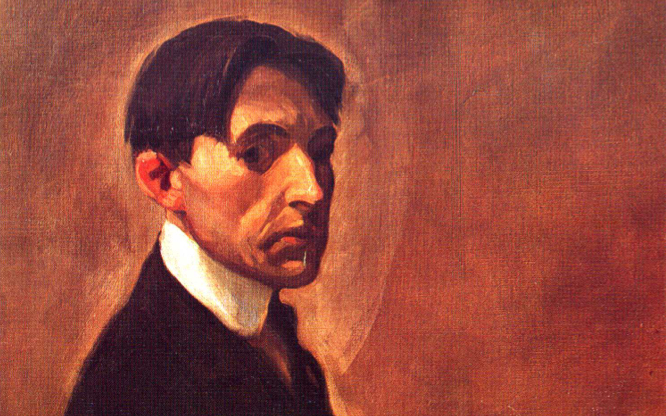

R: Detail of self-portrait in Memory (1906) Etching on paper

Click image to enlarge.

He even notices that the hairdresser's glasses and stub nose resemble the artist's. Compare them to one of Sloan's self-portraits at left.

He adds that this androgynous change is announced in a sign next to the hairdresser's window. It reads "Madame Malcomb" but the word "Madame" seems to be crossed out by a horizontal shadow, as if to imply that Madame Malcomb is not a woman but a man.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Lobel goes on to observe that the building's facade is so crowded with signs that it resembles how gallery walls were hung in contemporary exhibitions. One is even titled Ung Low Chop Suey, a pun on how artists used to describe the best position on a gallery wall. They invariably wanted pictures "hung low", not up near the ceiling where they could not be seen.

Not all Lobel's persuasive insights into Sloan's paintings of the period can be repeated here but his explanation of the hat circled with colorful flowers in the lower right corner should be. It represents, he writes, an artist's palette, in both its shape and colors.

Click next thumbnail to continue

In another painting the same year Sloan depicted revellers in the streets waiting to celebrate election results. Lobel notes that a man dressed all in black holding a "tickler" - a long stick glued with feathers at the end, a popular novelty at the time - faces the canvas like the artist would have when "painting" the scene in front of him, the feathered stick a substitute for the artist's brush. You can see him on the right, his right arm raised and extended like a painter's.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Sloan's 1910 painting, Clown Making Up, is another example. Lobel describes it as a picture "of someone applying pigment - in other words, paint - to his face" and comments that the box of makeup on the table "bears a close resemblance to a painter's palette."2

The idea that the clown is painting his own face is, of course, identical to how this website has long described Nana in Manet's eponymous painting, an image that Sloan would have known.3

See conclusion below

Lobel's ability to interpret Sloan's art as accurately as he has done is a rare. As a specialist, he naturally thinks that Sloan's habit of turning scenes of contemporary life into allegories of art is peculiar to Sloan and, perhaps, one or two other artists. He credits Michael Fried for similar conclusions about several of Courbet's best-known paintings but seems unaware of EPPH.4 Regardless his contribution is welcome as further confirmation of art's basic paradigm and its traditional methods. Strangely, it appeared in the same issue as Joost Keizer's article, "Michelangelo, Drawing and the Subject of Art", in which he argues that Michelangelo's lost-Cartoon for the Battle of Cascina is despite the apparent scene also about art but more on that next week.

More Works by Sloan

Notes:

1. Lobel, "John Sloan: Figuring the Painter in the Crowd", Art Bulletin 93, Sept. 2011, pp. 345-68

2. ibid. p. 365

3. Lobel notes that Sloan and other members of the Ashcan School would have been familiar with Manet's paintings, as well as those of Courbet and the Impressionists. (Lobel, ibid.,p.346)

4. Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (University of Chicago Press) 1990, pp. 81-2, 105, 133, 167, 198

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 03 Oct 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.