Monet’s Camille Monet in the Garden at Argenteuil (1876)

Monet, Camille Monet in the Garden at Argenteuil (1876) Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Click image to enlarge.

Classifications in art are rarely helpful based usually on superficial appearances and the lowest common denominator. Genres, beloved by institutions, have been one of the most misleading. Is this painting by Claude Monet, for instance, landscape or portraiture? Said to depict, as the title suggests, Monet's wife in the garden, her figure is small and incidental and, as conventionally pointed out, dwarfed by nature.1 Why?

Click next thumbnail to continue

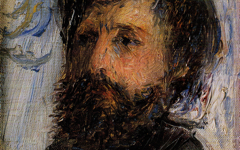

L: Monet's Camille Monet in the Garden at Argenteuil (detail)

R: Benque, Photograph of Monet (c.1880)

Click image to enlarge.

Monet is depicting not his garden but his mind. His head, constructed out of foliage, takes up most of the image and is its focus. Compare it to the contemporary photograph at right. His head in the canvas faces us while that in the photograph is turned to one side. Nevertheless, his evanescent portrait is quite apparent as a mental image in his mind, a mind as fertile as his garden.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Camille, as his favorite model, spiritual soul-mate and feminine alter ego, stands next to the trunks of two trees resembling long legs that then become Monet's hair, forehead and eyes. Together, he and Camille make his mind androgynous and part of nature. There is a possibility, too, that the long, thin trunks and their bending branches, flush with foliage, are visual metaphors for his brushes while the multi-colored flowerbed over which they hover may represent his palette. If so, both are important unseen metaphors that pervade his art.

Be that as it may, this landscape is a portrait and by no means unique. You can find Monet's face in all sorts of canvasses, as in Monet’s Rouen Cathedral (1892-4). Nor is he alone. Hundreds of other artists, fully aware that every painter must paint himself, have done likewise; you can find some other examples under the theme, Veiled Faces.

More Works by Monet

Notes:

1. Colin B. Bailey in Masterpieces of Impressionism & Post-Impressionism: The Annenberg Collection. (Philadelphia Museum of Art) 1991, pp. 54–55, 164–65; Gary Tinterow in "Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 1999–2000", Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 58 (Fall 2000), pp. 5, 44–45. Bailey, in meaningless seriousness, comments on this painting that the garden of the house is evidence of Monet's "bourgeois aspirations". Naturally, he failed to see any humor in its address: 21, Boulevard Karl Marx.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 23 Jan 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.