Parmigianino’s Allegorical Portrait of Emperor Charles V (1529-30)

Does an allegorical portrait, like the one below, have the same meaning for everyone? If it does, then this portrait by Parmigianino depicts Charles V being offered a sprig of olive by the winged figure of Glory while a young Hercules holds up the globe in reference to Charles’ empire. That’s it. Is that poetry?

The only other fact of any interest is that while most scholars believe the painting is by Parmigianino himself, a sizeable minority think that the Emperor's figure, presumably the most important element in the composition, is so poorly painted that the artist must have allowed a lesser colleague to paint it.1 That’s strange. Why would Parmigianino leave Charles’ figure and face to a pictorial hack?

Perhaps the most graceful element is the foreshortened hand of Glory but what is she doing? Even a cursory glance suggests something is wrong with the story as initially suggested. Winged Glory, when you really look, seems to be offering a ridiculously small twig, not to the Emperor as we expect, but to his elbow. She does not even look at him, nor he at her.

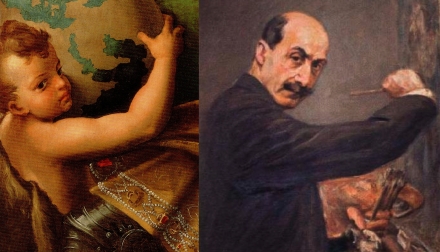

Left: Detail of Hercules in Parmigianino's Portrait of Charles V

Right: Detail of Max Liebermann's Self-Portrait (c. 1915)

Click image to enlarge.

One hint, for regular users, is the young Hercules. In a pose we have discussed elsewhere, Hercules looks out over his shoulder as artists do when painting their own portrait in a mirror. Hercules, his arm raised, represents an artist at the peak of his divine powers, reborn spiritually-speaking as a child.2

Parmigianino also imagined Glory as an “artist” about to paint the Emperor’s arm with her olive “twig-brush.” That is why she stares so intently downwards at the “brush” and at the arm she is "painting". It is also why the painted Emperor, depicted in a different style (taken for another hand by connoisseurs) lacks any sign of life. He is a “painting.”

Both male Hercules and female Glory are "artists", the two gendered halves of the painter's whole and androgynous mind.

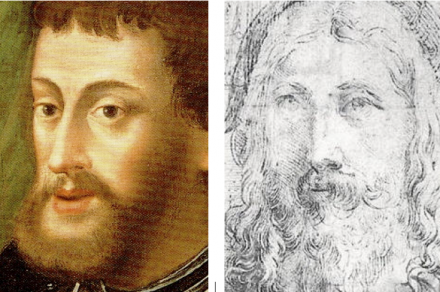

Left: Detail of Parmigianino's Portrait of Charles V

Right: Detail of engraving after Parmigianino's Self-Portrait

Click image to enlarge.

Every painter paints himself, of course, so the Emperor’s face, like that of so many other rulers shown on this site, must represent the artist too. He does, for example, have a family resemblance to Parmigianino (near left). Charles is the artist as ruler in Parmigianino's fertile and creative mind.

I am no connoisseur (and have never seen the original) but the idea that the Emperor's lifeless figure was painted by someone else now carries less weight. Indeed even if an assistant did paint it, the master would have given directions and was presumably satisfied with the final painting. Whatever took place in the studio, the master intended Charles to look stiff like a painting, the style intentionally different. (Artists like Rubens and Manet used the same method too.) That is why it is sometimes more useful to note the problems scholars have with a work of art than with their understanding. The problems can offer a short-cut to a different form of visual perception, to the scene that has rarely been seen.

See conclusion below

Parmigianino was a practicing alchemist used to metaphorical language as code for spiritual truth. Indeed, for spiritual alchemists, all knowledge worth having would have been veiled, verbally or visually. That is why it is impossible to believe that any painting by Parmigianino would be based on a straightforward understanding of the scene as though a title like Glory and Hercules Honoring Charles V would be enough. He would not have wanted all viewers to see what he had painted. That is not how art works and even if the above painting is not the greatest or most interesting in the world, it is now, at least for me, more interesting. There is, of course, much more to explain and no doubt more to see as well but until the observer can grasp the poet's primary understanding of what we are looking at, all else is in vain.

More Works by Parmigianino

Notes:

1. Titien: Le Pouvoir en Face (Paris: Musée Luxembourg) 2006, p.86

2. Hercules' thumb is stretched away from his other fingers as a painter’s thumb is when straining to fit through the palette-hole. The fur wrapped around him may likewise be a subtle reference to the hairs of a paintbrush.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 22 Mar 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.