Peale’s Portrait of George Washington (c.1780)

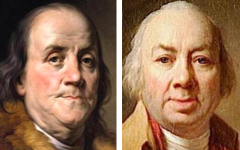

Charles Willson Peale, one of the most interesting nineteenth-century artists in America, studied painting in London under another expatriate American, Benjamin West, who painted a portrait of his star-pupil. In 2004 David Ward wrote of West's painting: “This portrait [of Peale] has less to do with creating a realistic likeness than with fulfilling the sitter’s and his audience’s expectations of what a mid-eighteenth century artist should look like. It might even be suggested that West subsumed Peale’s likeness to a generalized image of the artist; the retroussé nose looks less like Peale’s than West’s own as he painted himself...."1

Charles Willson Peale, Portrait of George Washington (c.1780) Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Click image to enlarge.

Peale's own full-figure portrait of George Washington is even more evidently about the artist than the sitter. It is a useful warning that those who seek historical facts from such portraits are on the wrong path. They might as well read a screenplay from Hollywood.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: C.W.Peale, George Washington, miniature (c.1777) Watercolor on ivory in gold bracelet mount. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Right: Peale, Self-portrait with Angelica and Portrait of Rachel (c.1782-5), detail inverted

Click image to enlarge.

An earlier portrait of Washington by Peale (far left) is an even clearer fusion of Washington's young face with Peale's though the self-portrait at near left post-dates it. [There is likely to have been a similar, earlier self-portrait now lost.] The difference in the President's apparent age between his two portraits, both painted by Peale only three years apart, strongly suggests that at least one looked little like him.

Click next thumbnail to continue

In the later painting, the one with less facial resemblance, the artist himself - never recognized as such before - stands in the background as the President's groom, his hand stretching towards Washington as though he was painting him....No wonder the figure is on a totally different scale.2 The President is a "painting"; the groom is "painting" him.

Click next thumbnail to continue

That groom not only resembles Peale's self-portrait (inset) from the Revolutionary War but so does the horse. The groom's eyes look to the left, unlike Peale's, but the horse looks out at the artist in the same way with similar eyelids and eyebrow. Peale even shaped the equine mane into a P for Peale with bayonets pointing at the horse's eye as hidden symbols for "paintbrushes."3 The general's hand (see fig.1) rests on the canon, yet another metaphoric brush, which though aimed at his groin (metaphorically fertile) opens as if towards us.4 The black "eye" of the canon (imagination) looks out at the artist while the general's hand (craft) rests on it.

Now let's look at the flags on the ground.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Detail of Peale's George Washington, rotated

Center: Detail of Peale's George Washington

Right: Diagram of detail at far left

Click image to enlarge.

Click on the the images at left to enlarge and compare them. Then see how the the left-side of the horse's head is suggested in the flags. Like painted fabric in the Renaissance or the broken forms of Cubism, Peale fragmented shapes (mental images) in his metaphoric canvasses (the flags). The horse, a visual homonym of a four-legged easel, is already in the "canvas" (flags) as if it is a mental image of the painting during its own creation.5

See conclusion below

Peale's portrait of America's first President may not be as artistically significant as papal and imperial portraits by Raphael and Titian but its subject matter, despite less subtlety in execution, is no less poetic. For similar examples by both earlier and later artists, see Dürer's Self-portrait as Christ (1500), Rembrandt and the Artist's Gold Chains, Van Dyck's Emperor Charles V and Titian's too, Rubens' The Four Philosophers (c.1611-12), Velazquez’ King Philip IV in the Frick Collection (1644) and Picasso's An Artist (1968).

More Works by Peale, Charles Willson

Notes:

1. Ward, Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic (Berkeley: University of California Press) 2004, pp. 31-3

2. The groom's hand held beneath the horse's head is strongly reminiscent of Picasso's own as an ephebe in Boy Leading a Horse (1906), a gesture already shown to be that of a painter.

3. The P is placed on the horse's forehead in front of its brain.

4. The opening of the canon's bore is too circular to be aimed leftwards as the barrel suggests; it ought to be more oval. The face of the canon's barrel, in seeming contrradiction, twists towards us.

5. Even the motto's banner (dotted lines in the diagram) echoes the bridle's strap while the upward-pointing cones of the horse's ears are inverted in the downward-pointing lines. The rosette below the image of the horse's head in the flags resembles the upper teeth of a horse with its mouth open while another, below it, seems to resemble the inside of its lower jaw.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 14 Feb 2013. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.