Rembrandt’s The Stoning of St. Stephen (1625)

Rembrandt, The Stoning of St. Stephen (1625) Oil on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

Click image to enlarge.

Rembrandt's first known painting, The Stoning of St. Stephen, seems to illustrate the death of Christianity's first martyr. Through the artist's eyes, however, the men executing Stephen would all represent himself executing an artwork of the saint alone whose raised but empty hand resembles that of the foreground executioner because Stephen too is an artist.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Left: Rembrandt, Detail of Self-portrait (c.1628-9) Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Center: Rembrandt, Detail of The Stoning of St. Stephen

Right: Rembrandt, Detail of Sheet of Studies with Head of the Artist (1651)

Click image to enlarge.

It is not surprising then that at least two of the killers resemble Rembrandt himself, as first noted by Perry Chapman in her 1983 dissertation.1 To my eye, though, the saint does too.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (completed 1475) Oil on wood. National Gallery, London

Click image to enlarge.

Rembrandt, however, did not exactly invent the idea. It had been used, for example, in 1475 by the Pollaiuolo brothers for their Martyrdom of St. Sebastian in which three pairs of crossbowmen take up similar poses. Far too close to their target for shooting, the six men are painting the nude figure of St. Sebastian which thus explains his nudity. Antonio had earlier composed something similar in his celebrated engraving, The Battle of Naked Men, which, of course, allegorically describes the engraving of naked men.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Michelangelo, Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs with detail of Phidias (c.1492) Marble. Casa Buonarotti, Florence.

Click image to enlarge.

Michelangelo's earliest known work is similar even though a different story. As I explain elsewhere, the Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs depicts the struggle in his mind to conceive and create the work. Vasari noted that Michelangelo placed the bald sculptor Phidias at far left (detail). He throws a stone made from stone while "making" the sculpture.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Rembrandt, The Stoning of St. Stephen (1625) Oil on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

Click image to enlarge.

When Rembrandt chose stoning for his earliest work too, he placed a killer's foot in the lower right corner where signatures go. His raised arm, must therefore be in our space or, more correctly, in the studio. So too with the men in shade, two of whom wear turbans as painters often did.2 The perspective and proportions are also inconsistent, leaving unclear the exact position of the saint relative to the men at left because he, as noted, is in a different reality.

See conclusion below

Rembrandt's identification with the saint's executioners helps explain why he later appeared in The Raising of the Cross as one of Christ's executioners as well. In each case, as described in the entry on The Raising of the Cross, Rembrandt executes the painting. His identification with the killers, though, helps demonstrate that he did not believe in an external God nor in one who judges men and punishes sinners. To the mystic and the early Christian too, God is part of us and all men are capable of doing good and bad; such actions are just part of who we are and nature. Death is used, though, as a metaphor for theosis, the moment when the artist's mind becomes at one with God's. At those moments of clarity artists are a vehicle for a greater power to express the unchanging Wisdom of man's nature and the cosmos in a work of art.

More Works by Rembrandt

See the sight which changes the meaning of all Rembrandt's art: Rembrandt is Christ

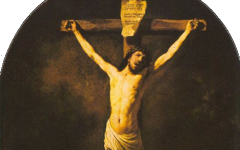

Rembrandt’s Crucifixion (1631)

Notes:

1. Perry Chapman, The Image of the Artist: Roles and Guises in Rembrandt's Self-portraits, PhD dissertaion (Princeton University) 1983, p. 242

2. See Abrahams, "Filippino Lippi’s Dead Christ and the Artist’s Turban" (Nov. 2011).

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 25 Sep 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.