How Portraiture Causes Blindness

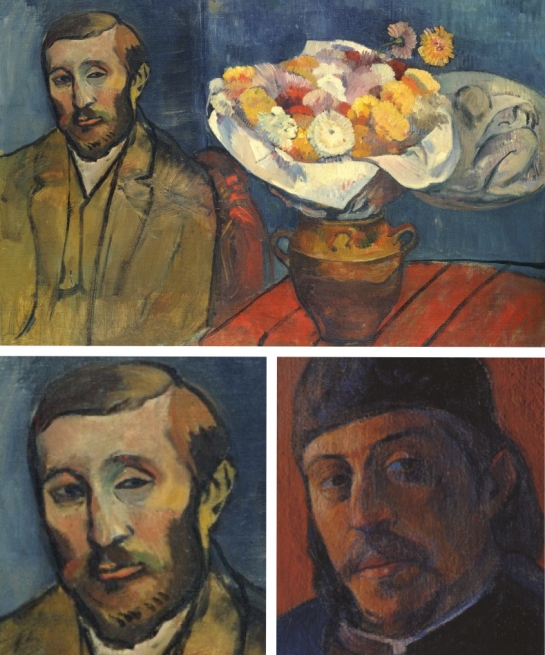

Top: Gauguin, Portrait of the Painter S. (Wladislaw Slewinski) (1891) Oil on canvas. National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo.

Bottom L: Detail of above

Bottom R: Detail of Gauguin's Self-portrait with a Palette (c.1894) Oil on canvas. private Collection.

Specialisation has crippled art history, blinding its practitioners to what is common. For over six years EPPH has been arguing that many portraits by major artists are fusions of the artist's facial features with the sitter's. They were never intended (by the artist, at least) as an accurate likeness. The method began even before portraiture reappeared in the 15th century after a 1,000 year absence.

It warms my heart then when I find a specialist discovering face fusion in the work of the painter they study. It does happen occasionally. Yesterday I read an article on Gauguin from 1998 by Władysława Jaworska. She wrote that Gauguin often gave his sitters traits typical of his own self-portrait. The picture of a Polish artist in Paris (top) was cited as an example.1 It is fairly obvious when you put the Pole's face next to a self-portrait by Gauguin (bottom). The same, though, is abundantly clear in works by Raphael, Titian, Rubens, Rembrandt, Ingres, Manet and dozens of other artists, major and minor. Why this general fact is never recognized by academics is the result of art's faulty paradigm. It blinds them because you see what you think. Viewers were, and still are, so certain that most portraits are accurate likenesses that that is all they can see: a visual copy of the sitter. This demonstrates the importance of questioning paradigms because all you really need to know to open your eyes is what we say here every day: every painter paints himself. As did Gauguin.

1. Władysława Jaworska, “Christ in the Garden of Olive-Trees by Gauguin. The Sacred or the Profane?”, Artibus et Historiae 19, No. 37, 1998, p. 88

Posted 02 Dec 2014: Artist as PoetArtist as Another ArtistGauguinPortraitureTheoryVisual Perception

The EPPH Blog features issues and commentary.

Reader Comments