The Poetry of Turner’s Eyesight

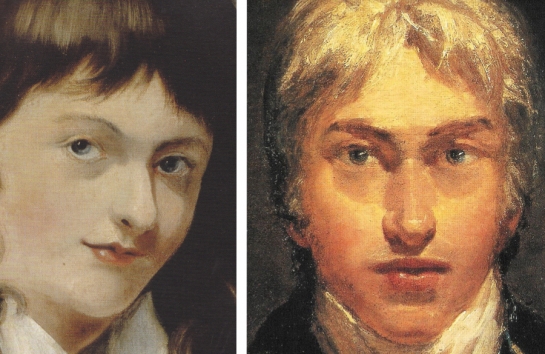

L: Turner, Self-portrait at the Age of Sixteen, detail (c.1791) oil on canvas. Indianapolis Museum of Art

R: Turner, Self-portrait, detail (c.1798-1800) Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

Artisans everywhere rely on the physical processes of sight. In the past that obvious fact was the basis of too much "interpretation". Impressionist paintings were said to have no meaning because they were exact reproductions of what the artists saw. And I must admit I too swallowed that one. I also believed on received "wisdom" that poor vision created El Greco's breathtaking style. And the sketchiness of late Titian and, more recently, late Turner, have both been ascribed to aging eyes too.

L: Turner, The Morning after the Deluge (c.1843) Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

R: Snow Storm, Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812) Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

Few have noticed, though, that Turner’s images throughout his career are often dominated by eye-shapes as EPPH has shown in those pictures already examined. Here are two more, painted 30 years apart (above.) At least one academic has noticed this.1 The difference is, though, that EPPH can state with confidence that these are not just ocular forms but meaningful depictions of Turner’s own dark-ringed eyes. You can see them in both self-portraits (above.) And from the evidence we have accumulated on so many other artists, we can infer that Turner's compositions are not landscapes or seascapes at all (in fact he painted them in the studio) but mind-scapes inside his head.2 They are visions of his own imagination at work, forever forming the compositions we see. We can actually see him fuse the visual data obtained through his eyes with pre-existing knowledge of universal significance stored inside. The combination is not unique to Turner being instead the basis of human sight. Most of us though, being less wise, fuse vision with ego-driven concerns, not wisdom. Artists, scientists and philosophers know this but few others seem to. Remarkably, knowledge of this process is not even a product of modern science but has been passed down in Western art since at least the 15th century, at a time when Chinese artists started calling landscapes mindscapes too.

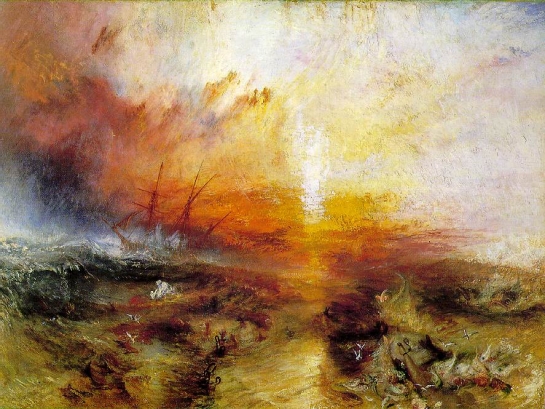

Turner, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and the Dying. Typhoon coming on (1840) Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

In this 1840 painting of a slave ship Turner's two black-ringed "eyes" are clearly visible, one underneath the ship, the other near the right edge (above.) The bridge of Turner's nose can be seen lit up in the sea between the eye-forms with the rest presumably beneath the lower edge. It follows then that the blazing sunset, emerging from a point between the eyes with light flashing upwards, is in his mind in the space behind his forehead. And, in a nice touch, the white crest or sail in the left-hand "eye" resembles a painted highlight in the painted eye of a portrait!

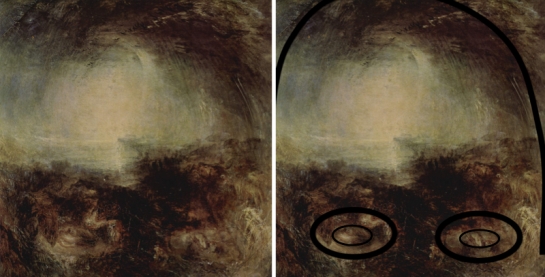

L: Turner, Shade and Darkness - The Evening of the Deluge (1843) Oil on canvas.Tate Britain, London.

R: Diagram of image at left

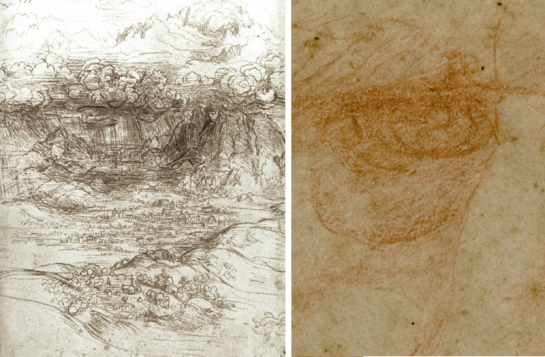

In Shade and Darkness - The Evening of the Deluge (1843) his eyes are again at the bottom with the storm above emerging in his mind as indicated by the contour of his head. (See diagram.) It is quite likely that Turner already knew of Leonardo's celebrated drawing of a deluge which experts also describe as a precise description of nature (below left).

L: Leonardo da Vinci, Storm over the Alps (c.1499) H.M. Queen Elizabeth II, Windsor Castle.

R: Leonardo, Self-portrait, detail of the artist's left eye inverted.

In 2011, however, EPPH showed that Leonardo's drawing is in fact based on his own left eye inverted. (See comparison above.) Leonardo did, of course, observe nature closely but depicting it accurately was not his main objective. The storms by both artists really depict the creative struggle inside their own minds to create the picture by fusing what they had observed in nature with wisdom inside. Turner could easily have developed his composition independently of Leonardo but, given that Leonardo's Storm was in the Royal Collection at Windsor, he may well have seen it. Meanwhile remember EPPH's definition of an artist: they are philosophers, not illustrators.

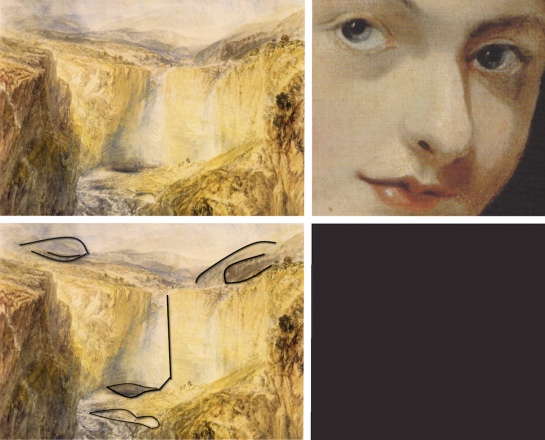

Top L: Turner, High Force, Fall of the Trees, Yorkshire (1816) Oil on canvas.

Top R: Detail of Turner's Self-portrait at the Age of Sixteen (c.1791)

Bottom L: Diagram of above.

In a somewhat different scene from 1816 (top left) Turner probably used his earliest extant self-portrait from around 1790 given the slant of the eyes in the distance near the top and his fully-formed lips with a prominent philtrum (top right). Try comparing the two with my diagram (bottom left.)

Turner, Lake Lucerne. The Bay of Uri from above Brunnen (c. 1841-2) Watercolor on paper. Tate Britain, London.

I could go on indefinitely. But, to avoid boring you, I end with a series of watercolors which Turner, an inveterate traveller, made of Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. Initially, the compositions seem quite different to those we have already examined, perhaps not even suggesting a face at all as in the example above.

Turner, Lake Lucerne. The Bay of Uri, from Brunnen (c. 1841-2) Watercolor on paper. Tate Britain, London.

In this version though two dark-ringed eyes become clearer on either side, a darker patch on the right even suggesting a pupil. Water, of course, was very important to Turner, no more so than in his watercolors where, in compositions like this one, the medium of water represents itself. In watercolors depicting rougher weather Lawrence Gowing noted a link between "the wonder and terror of the moment" and "the uncontrollable hazards of watercolor which were the medium of Turner's private, imaginative life."3 Besides the surface of water and its reflections have traditionally been associated with the surface of the reflective mind, calm when at peace, stormy in turmoil.

Turner, Morning on the Lake of Lucerne; Uri from Brunnen (c. 1841-2) Watercolor on paper. Tate Britain, London, London.

In a further watercolor (above) the eye-shapes and a pupil become even more evident as their forms are symmetrically reflected in the water.

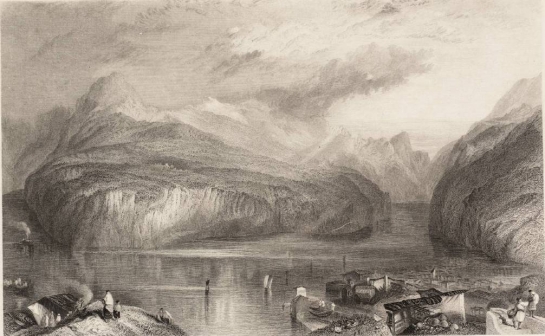

Turner's Lake of Lucerne from Brunnen engraved by Robert Wallis

I cannot find a good reproduction of the last example in the series. However, in an engraving that Richard Wallis made after it the eye-form that Wallis clearly perceived in the original leaves no doubt that all these sketches of Lake Lucerne (whose French name is even derived from a word for light) are based on Turner's eyes. Like all the images shown, the engraving depicts the sight behind Turner's eyes and not in front. Indeed hundreds of other seascapes and landscapes by many other artists are waiting to be seen as similar mind-scapes. So use your own eyesight. Don't trust, like I once did, what everyone else believes. And don't pass them by as a pretty picture or a postcard-view by a traveling draughtsman. Look more closely through the artist's own eyes to the perennial philosophy in art, changed and adapted by a succession of artists to the lifestyles and concerns of each culture and each new generation. That's what the best contemporary art does too. Yet, while ordinary painters and sculptors have always been common, visual philosophers like Turner are as rare as Tyrian Purple.

Notes:

1. Simon Schama, The Power of Art (London: Ecco) 2006

2. See Turner's The Fifth Plague of Egypt (1800), The Shipwreck (1805) and Undine Giving the Ring to Masaniello (c.1845-6)

3. Lawrence Gowing, Turner: Imagination and Reality (New York: Museum of Modern Art) 1966, p.53

The EPPH Blog features issues and commentary.

Reader Comments