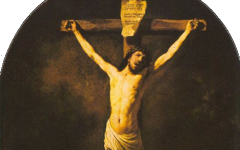

Rembrandt’s Raising of the Cross (c.1633)

This painting of Rembrandt crucifying Christ is an excellent example of the alternative way to read art, not viewing it as an illustration but as poetry. To call it The Raising of the Cross, as both the patron and Rembrandt would have publicly, is to describe its lowest common denominator, as an illustration of the Bible.1 Take it as a general rule, though, great masters never illustrate. Think of it instead through Rembrandt’s viewpoint as The Artist Struggles to Depict “The Crucifixion”. Rembrandt is the spot-lit figure in the beret and, accompanied by studio assistants or other representations of himself, he struggles to raise his work of art “The Crucifixion”.2 The scene is a visual metaphor for the struggle in his own mind to create his painting and art’s archetypal subject is not The Raising of the Cross but The Crucifixion. [For a very similar example, see "The Craftsman's Christ".]

Overseeing "the studio scene" is a white-turbaned commander who also resembles self-portraits by Rembrandt. Positioned behind the Crucifixion scene, he seems to both look out of the painting and observe the action. However, as another alter ego of Rembrandt, he is not looking out at us but into the mirror of his own mind. His historically inappropriate turban is also significant because artists often wore turbans in the studio to keep paint off their hair and sometimes, like Jan van Eyck, donned them in their self-portraits too.

Click on the next thumbnail

Keep this understanding in mind when you see other paintings of this subject. Rubens and Tintoretto, for example, constructed their versions of the story on the same basis: studio hands, some in contemporary clothing, struggling to raise the artist's supreme artwork: the artist as Christ crucified.

Text continues below

One last observation is that the lighting is central to Rembrandt's meaning. Not only does the light on Christ separate the two levels of reality, the studio and the work of art, but also alludes to the spiritual journey that Christ’s life is a guide for. The spectator’s viewpoint (Rembrandt’s really) beyond the dark of the freshly dug grave suggests that we too must go from the darkness of our current life to the light of the next, once we reach, dead or alive, union with the divine and find the Christ within ourselves. It can be a struggle to get there.

More Works by Rembrandt

See the sight which changes the meaning of all Rembrandt's art: Rembrandt is Christ

Rembrandt’s Crucifixion (1631)

Find out why people pee on etchings

Rembrandt’s Man Making Water (1631) and Woman Making Water and Defecating (1631)

Scholars have long wondered why Rembrandt would represent himself in expensive and extravagant clothing from a century earlier even though they know that the etched self-portrait is based on an engraving of the fifteenth-century painter Jan Gossaert, known as Mabuse.

Rembrandt’s Self-portrait in Sixteenth-Century Costume (1638)

Notes:

First published online in April 2010. Reissued June 2012.

1. Conventional experts tie themselves in knots to explain why Rembrandt would depict himself as evil. One proposed that Rembrandt is “confessing”, that in murdering Christ he is identifying himself as a sinner. What did Rembrandt do? Kill someone? Another believes that the painting was intended as a promotional tool though it beggars belief why crucifying Christ would have been good for business. Rembrandt was neither so religious nor so foolish; he was a poetic painter who like all great artists portrayed the processes of his own mind. For the confession see Ingvar Bergstrom, “Rembrandt’s Double-Portrait of Himself and Saskia at the Dresden Gallery: A Tradition Transformed”, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 17, 1966, p. 166; For the promotional role, see. H. Perry Chapman, The Image of the Artist: Roles and Guises in Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits, PhD diss. (Princeton University), 1983, p. 243

2. The Crucifixion within the painting might represent a sculpture, an equally good symbol of art, because the scene itself looks so much like workers trying to push a heavy marble piece upright onto its pedestal. It could be that Rembrandt saw mental images of his paintings in 3-dimensions, as some composers have said of their own work.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 28 Jun 2012. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.