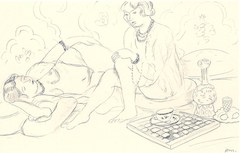

Matisse’s Marguerite (1906-7)

In the autumn of 1907 Matisse and Picasso decided to exchange paintings. Picasso chose Matisse's portrait of his daughter Marguerite (left), a simple composition and a seemingly strange choice. Gertrude Stein said the two artists each chose the worst example of the other's painting; friends reported that Picasso mocked Matisse's picture by throwing darts at it. Both accounts reflect the ignorance of the spokesman because Picasso had great respect for the Frenchman and his art. What, then, did Matisse paint and what made Picasso choose it?

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Velazquez, Portrait of Infanta Margarita (c.1655) Louvre, Paris.

Bottom: Diagram of a detail

Click image to enlarge.

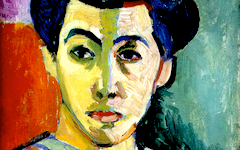

First of all, he would have recognized that Matisse based his daughter's portrait on a then-celebrated painting in the Louvre by Spain's great master, Velazquez (left).1 It depicts the Infanta Margarita, the namesake of Matisse's daughter and the star of Las Meninas. Her name is similarly written across the top. Note, though, how Velazquez used the black brocade on her front as a prominent V while placing a second smaller one in the central space between the petals of the rosette (below). The latter is directly above one of those gold chains great masters like Velazquez so desired. [See State Honors.]

Picasso surely knew Edouard Manet's many hidden references to Velazquez's self-representation as the Infanta, most still unpublished. [See Manet's Olympia] Thus Matisse's daughter represents not only Matisse but Velazquez and Manet as well.2 The latter were two of Picasso's great heroes in art, one from Spain his native land, the other from France his adopted country.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Degas, Marguerite, the Artist's Sister (c.1863) Oil on canvas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

R: Velazquez, Portrait of Infanta Margarita

Click image to enlarge.

Forty years earlier Degas used the Infanta for the same purpose, basing the portrait of his sister, also named Marguerite, on Velazquez's namesake-princess. He was probably not the first to do so and Matisse was not the last. Thus the Infanta's traces in art history are both long and complex.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top L: Diagram of Matisse's Marguerite showing a phallus on her head

Top R: Diagram of Velazquez's Infanta Margarita showing paintbrush on her head with handle added.

Bottom: Detail of Matisse's Marguerite

Click image to enlarge.

Now to the interesting part. Sexual conception is an overlooked metaphor in art for mental conception. No-one has noted how Matisse used it to shape his daughter's hair into an ejaculating phallus (left). He did so because the Infanta's hair on the same side is shaped like a brush drawing a dark line down her temple (right, with handle added). Both are the painter-as-model.

Artists have long linked brushes to phalluses so Matisse's metamorphosis is hardly surprising. In the 16th century Bronzino wrote a poem connecting the variety of sexual positions with those of a brush while Renoir, in the 20th, referred to his brush as his own penis ‘licking’ the surface of his canvas.3 Picasso's images leave no doubt either: his artists hold their paintbrushes near their groin.

Now see the line dividing Marguerite's nostril in two. It represents shading but, crudely drawn, draws attention to itself. Why?

Click next thumbnail to continue

Turn the painting upside down and you can see the form of the letter 'h' for Henri in her dress and an "m" for Matisse in her nose. Just as Velazquez placed his own initial in the center of Margarita's chest, so did Matisse on Marguerite's. You can find more such examples by both painters under the theme at left, Letters in Art.

Matisse's portrait may seem simple at first but is full of art. Picasso's eyes, trained on Velazquez and Manet, would have seen his rival's method and known that few others would see anything at all - including his own friends. It was the secret of two great artists, French and Spanish like the sources. And, if this is still 2014, you are one of the first ever to see it.

For a similar portrayal a year earlier, see Matisse's portrait of Mme. Matisse known as The Green Line (1905).

More Works by Matisse

Notes:

1. The painting was then thought to be entirely painted by Velazquez and was a celebrated artwork in Paris. Nowadays, the issue of authorship is not so clear though all agree that it was painted in Velazquez's studio under his direction if not by him personally. It is therefore painted the way he wanted it and that's what matters.

2. See Manet's use of an artist's daughter in The Railway (1873).

3. Agnolo Bronzino, Rime in burla, ed. F. Petrucci Nardelli, Rome, 1988, pp.23-6; Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father (Boston: Little, Brown) 1962, pp. 205-206.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 11 Feb 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.