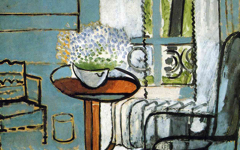

Matisse’s The Green Line (1905)

Matisse, The Green Line or Portrait of Mme. Matisse (1905) Oil on canvas. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Click image to enlarge.

In 1905 Henri Matisse exhibited this portrait of his wife to a shocked art world. She has a green stripe down her face. Now a Fauvist icon, The Green Line as it is known has been studied for a century yet revealed little. Many comment that Matisse was primarily interested in decoration, allowing color to dictate form. That sounds wrong because form conveys ideas more than color. And, within EPPH's definition of art, self-representation is required too. These are, we argue, essential characteristics without which Matisse's works would not have been admired for so long even if a lot remains unseen. It seems that somehow there is an unconscious awareness in the art world of hidden content. I have examined The Green Line for years though and, like others, have seen little beyond a portrait. All I could see was the green stripe as perhaps a symbol of fertility penetrating her mind above. Yet I always thought there was more.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Detail of Matisse's The Green Line, rotated

R: Detail of Matisse's Self-portrait, rotated (1900) Oil on canvas. Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris.

Click image to enlarge.

Last night I rotated the picture and found what I was looking for: veiled content and meaning. In the block-like forms of Madame's coiffure resides the "face" of her husband with one "eye" only, all in black and dark blue. The large, circular form of a spectacle on the right; the triangular nose next to it; even the black shadow under his "beard". It resembles his face as seen in many self-portraits. The one at right is from five years earlier.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Mme Matisse, like the wives of many artists, is represented as the feminine version of his own self and the creative part of his androgynous mind. His "head" is in the darkness of hers which is really the creative, cave-like depths of his own imagination. Totally in line with tradition, Matisse represents the model as the artist; he unifies object and subject; and depicts not a true likeness of his wife (few great artists have done that) but a feminine version of his own Self at the moment of creation. Further looking will, no doubt, yield more meaning but not until the viewer acknowledges that this is self-representation and not what most call "portraiture".

The next year Matisse styled the hair of his daughter into a phallus. See Matisse's Portrait of Marguerite (1906-7), a painting Picasso owned.

More Works by Matisse

Notes:

1. The next year Matisse took similar liberties with the hair of his daughter as I have shown in Matisse's Portrait of Marguerite (1906-7), a painting Picasso owned.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 23 Oct 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.