Matisse’s Dance II (1910)

Here is a tip to improve your perception. No need to know the whole of art history. Just memorize the details of one or two really important works, like the Mona Lisa and Velazquez's Las Meninas, each repeatedly used in the novel compositions of later artists. Become so familiar with them that when one of their shapes turns up elsewhere, you will recognize it. Source-hunting, as it is known, is an essential tool for interpretation because, in visual art, a borrowed form borrows meaning. Matisse's Dance II is a good example.

Top: Matisse, Dance II (1910) Oil on canvas. The Hermitage, Saint-Petersburg

Bottom: Matisse, Dance I (1909) Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Click image to enlarge.

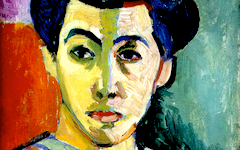

Dance II (top) depicts five nudes dancing in a circle on a grassy hill, a motif taken from Matisse's earlier canvas, Le Bonheur de vivre. There and in the initial study (bottom), all five figures are female. Yet no-one seems to have noted the obvious: that Matisse lengthened the figure on the left in the final version (top) and took away her breast. She has become male.

The only known reference in the two images are the almost-touching hands from Michelangelo's Creation of Adam. Both arms, though, like those in the Creation also represent the outstretched arm of a painter with the man's hand enlarged and floppy like a brush.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top L: Detail of Matisse's Dance II (1910)

Top & Bottom R: Detail of a self-portrait by Matisse drawn on a postcard (c.1915) Inverted and rotated.

Bottom L: Diagram of Matisse's Dance II

Click image to enlarge.

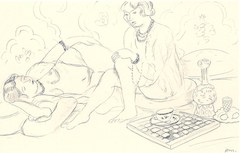

Perhaps inspired by a similar illusion in Michelangelo's Last Judgment, also in the Sistine Chapel and first revealed on EPPH, Matisse's self-caricature in Dance II is drawn like the ones he so often added to postcards and letters home (right). The figure's breasts become his glasses and thereby represent creative fertility while the contour of her rib-cage is the artist's nose, its nostril a line of shadow below. Matisse, though, could define his face by glasses and beard alone, the latter seen in the curved lines of her voluminous abdomen.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top L: Detail of Matisse's Dance II (1910)

Top R: Diagram of Velazquez's Infanta Margarita Louvre, Paris

Bottom: Matisse, Detail of Matisse's Le Bonheur de vivre (1905-06) Barnes Foundation, PA

Click image to enlarge.

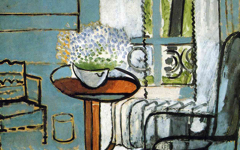

Matisse had already based the 1906 portrait of his daughter Marguerite [see entry] on Velazquez's namesake Infanta Margarita in the Louvre (2) who is the star of his later Las Meninas.1 Velazquez shaped her coiffure like a paintbrush because brushes are hair-like and art both comes from and depicts the mind "underneath". That's why Matisse also used a brush-shape for the hair of his central dancer (1) and depicted the reclining nude facing the motif of The Dance in his 1906 Le Bonheur de Vivre as if she were an artist contemplating her own picture with an emphasis, again, on the flow of her hair (3).

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Diagram of Matisse's Dance II

Middle L: Detail of Matisse's Dance II, rotated

Middle R: Detail of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam

Bottom: Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam Sistine Chapel, Vatican

Click image to enlarge.

As was his habit, Matisse inscribed an M for Matisse into the center of Dance II.2 And just as artists often identify with earlier artists, so he did with Michelangelo whose initial he shared. His tripping dancer is a divine painter descended from The Creation of Adam. The outstretched arms are like God and Adam's while she herself is almost horizontal like the flying figure who holds up Michelangelo's God and crew (center & bottom). Nude like her and seen from behind too, he is the Archangel Michael, a take on Michelangelo.3 Matisse's woman thus represents both Michelangelo and Matisse. Note too how the two blue hills behind Adam (bottom) are repeated in the two green hills in The Dance (top).

Click next thumbnail to continue

Lastly, the dwarf in the lower right of Las Meninas kicks a leg like the dancer on the far right, the dog as his target replaced by the butt of the "reclining" dancer from Michelangelo's Creation. Creation is the theme here too, as it is in Las Meninas. The dancer at upper right leans forward and looks down like the maid-of-honor to the right of the Infanta with a vaguely similar hairstyle. The dancer at left, its gender changed and made taller, takes the place of the tall Velazquez, also on the left. That leaves us with Matisse's "feminine" self-portrait positioned in the Dance where Velazquez's royal couple (male and female) is reflected in the mirror. Las Meninas is a circular dance like Matisse's (see red oval) so, consistent with EPPH's explanation of the Velazquez, Matisse placed his "self-portrait" where the mirror would be. Both symbolize the purity (and reflection) of the artist's eye which, as in alchemy, is both royal and androgynous as Matisse's figure of "Velazquez" is too.

See conclusion below

Once you recognize how an artist uses his various sources to veil meaning, everything becomes clearer. It explains, for instance, why on the surface the scene of Dance II is so mysterious and seems to mean so little; why the figure at left lost a breast and why the woman in the foreground has both odd-shaped hair and trips. The lack of meaning on the surface reminds me of how Les Bursill, an Australian aborigine, described the interpretation of his people's art: "Meaning is for those who are ready for it, for those who are trained for it. The rest get pretty pictures." Dance II is a pretty picture unless you know that all art represents the poet's own search for self-knowledge and that, as here, a borrowed form borrows meaning.

For a further link between this painting and the Sistine Chapel, see the brief post on "Magic from Matisse and Michelangelo".

More Works by Matisse

Look for the eyes. Then the face. Never forget to look for them because you can find them anywhere in art.

Matisse’s The Window (1916)

Notes:

Notes to be completed soon

1. See Matisse's Marguerite (1906-7).

2. Las Meninas is also constructed out of Velazquez's initial, a giant V extending from the upper two corners down to the Infanta's head.

3. Leo Steinberg, “Who’s Who in Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam: A Chronology of the Picture’s Reluctant Self-Revelation”, Art Bulletin 74, Dec. 1992, pp. 552-66; Bronzino also addressed sonnets to Michelangelo that acclaim him as both God and as the Archangel Michael. See Stephen J. Campbell, "'Fare una cosa morta parer viva': Michelangelo, Rosso, and the (un)divinity of art", The Art Bulletin 84, No. 4, p. 620, n. 109.

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 19 May 2014. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.